Odur Ronald: ‘Why is it easier for raw cotton to reach European capitals than for Ugandan people to travel anywhere?’

Ahead of the rescheduled Dakar Biennale, we spoke with Odur Ronald, whose distinctive works explore themes of power, mobility, and identity.

Growing up near the biggest scrap-dealing community in the Kampala suburb of Katwe, Ugandan artist Odur Ronald has transformed his childhood scrap-collecting experience into an artistic practice that insistently questions the Western concept of freedom. Aluminum-made copies of his family's house environments approximate viewers to the artist's life amid Uganda's political turbulence. A discrete list of objects – passports imprinted on metallic plates, bullets, banknotes, and jerry cans, among others – makes tangible a regime of violence and censorship whose long-term implications often escape any immediate comprehension.

A close-up of the cotton and copper flowers during Odur Ronald’s open studio at Gasworks residency. Courtesy the artist and Gasworks, London.

Giulia Menegale: Embossed aluminum is a signature of your artistic practice. What does it mean to you?

Odur Ronald: When I became an artist I couldn't afford paints, canvas, and so on, which led me to use materials I had collected during my childhood days. One day I saw someone embossing Coca-Cola cans on a YouTube video. Aluminum printing plates have a slightly thicker consistency than soda cans, but the raw material is the same. From there, I got the idea of embossing them. That was almost ten years go now.

GM: You use multiple techniques to work with aluminum – including basketry, weaving, and stitching, which are connected to African ancestral craft. Where did you get those skills?

OR: I got inspired by my mom. She is a teacher, but in her free time she enjoys making textile decorations with cotton yarn, sometimes with raffia. I use metal instead of yarn. My ancestors explored these techniques and passed them on to us. I can't say I invented something, I just borrowed them and then used another material to create my artwork.

A close-up of Women Resting, 2024, during Odur Ronald’s open studio at Gasworks residency. Courtesy the artist and Gasworks, London.

GM: Are these kinds of know-how connected to a traditional division of gender roles within families' economies?

OR: Of course. In my culture, women are the family members who design draperies and mats to make the house look welcoming. Whether they agree to it or not, they are also the ones who cook, look after kids, and clean the house. My body of work Women Resting (2021) critically comments on women having to complete all these duties during their limited free time. During my residency at Gasworks in London, I portrayed my sisters in resting poses on the surfaces of the mats that I wove with aluminum strips. I imagined the talents and potentials they might discover if they could use some of their time to express and nourish themselves.

GM: Often, your aluminum-made copies of domestic settings address Uganda's political corruption and violence. Stumbling across these scenes, someone might sense that something has happened, but no indications fully disclose the nature of the event.

OR: My artistic practice relates to biographical experiences. During the riots between protestors and police officers that followed the general election campaigns in 2020, my family house was filled with fumes from tear gas and stray bullets. I had thought of the private space as a safe environment, but suddenly it wasn't. Muwawa ("Without Care," 2021) responded to that violent episode. I replicated my living room space and added a chandelier of 1200 cast aluminum bullets suspended from copper wires. On the replica dining table, I placed various aluminum copies of objects such as Ugandan bank notes, a bottle of waragi (the local gin), a passport, and a box of cigarettes. I complete the scene with a 1990s-era television set, a Bible, and a real stone. Depending on which side of the table people find themselves at, they can access different types of power.

GM: Was this episode the first time that the Ugandan sociopolitical context influenced your work in such a direct manner?

OR: You must consider that I grew up in a country that has had a war going on – in the northern part of the country – for more than twenty years. Since the beginning of the Lord's Resistance Army insurgency in 1987, an intergenerational trauma has haunted my family and therefore my work. The studio is the place where I release my emotions.

A close-up of Waagawullide ("Have you heard it?"), 2024. Photography by Henry Robinson. Courtesy the artist.

GM: If I remember correctly, one of your aluminum-bullet works got "arrested" at the airport on its way to the 60th Venice Biennale.

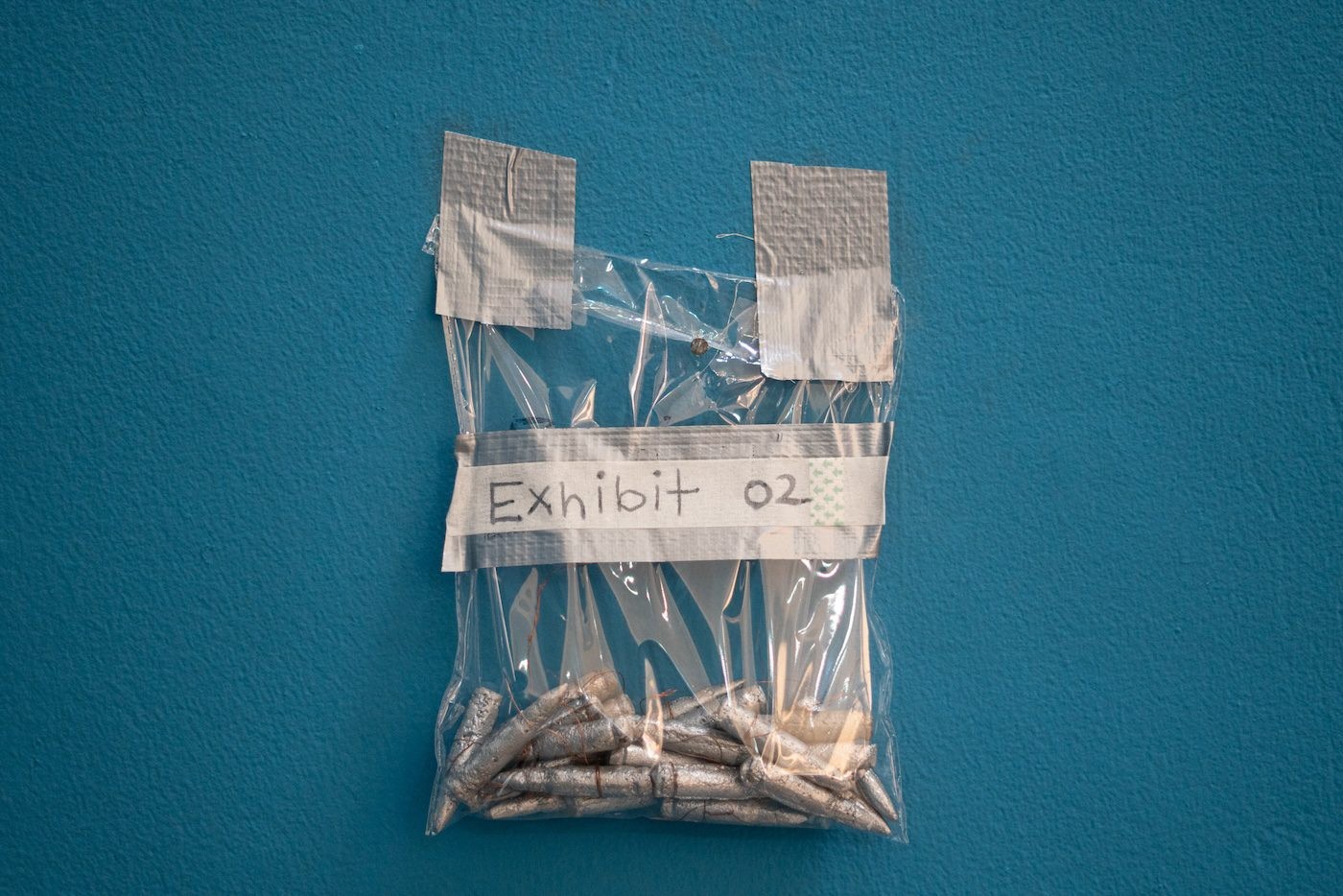

OR: The work was confiscated at the airport without a proper explanation from the local authorities. Due to the current political climate, I decided not to continue the project as I worried the situation might escalate. A few months later, for the group exhibition Beyond Sculpture (July–September 2024 at Kampala’s Afriart Gallery), I made the multidisciplinary installation Waagawullide ("Have you heard it?" 2024) to comment on the troubled relationship between artistic freedom and censorship in my country. I wrote "exhibit" on silver duct tape and stuck it on a transparent plastic bag holding newly produced aluminum bullets, similar to those meant to be shown in the Ugandan Pavilion.

A photo of the performance as part of Waagawullide ("Have you heard it?"), 2024, at the Afriart Gallery, Kampala. Photography by Henry Robinson.

GM: So which works did you present in Venice?

OR: I exhibited copper copies of passports, part of The Republic of This and That (2024). The installation showed the worth of those small booklets in the African context. I am working toward a new version of the work for the 15th edition of the Dak’Art Biennale.

GM: Tell us more about it. Having the Biennale been postponed from the spring to now—have you adjusted anything during the wait?

OR: The Republic Of This and That is a body of works that consists of several aluminum-made copies of fictional African Union passports suspended using copper wires. Installed in their proximities, the interwoven aluminum browned mats are objects that speak to me of the idea of collectiveness, especially regarding the strength we would achieve if only we were one, notwithstanding differences. Also, recently, I felt the necessity of going against what’s projected onto me as an artist from a colonial perspective. I want to take charge of defining my own art and inserting some surprises into my work.

Odur Ronald, The Republic Of This and That, 2024. Photography by Darlyne Komukama. Courtesy the artist.

GM: The Republic of This and That (2024) is not the only body of work in which you address mobility rights and freedom of movement.

OR: When I was in England, I started working on cotton and copper flowers after noticing that many UK trains only transport human beings. We also have trains reserved for people in Africa, but most of the railroads transport goods. And it's not the local government who constructed that infrastructure but British and German imperialism. This triggered questions for me about why it is easier for raw cotton to reach European capitals than for Ugandan people to travel anywhere. I must write an application and pay visa fees without the acceptance guarantee. With the cotton, you pay shipping fees and then it’s shipped by plane.

GM: Besides sculptures and painting, what other media are you exploring?

OR: For some time now I have also been working with performance. For example, Waagawullide is part of a multimedia installation engaging with archival videos from 1962, when Uganda won independence. It juxtaposes those images with a living picture of the country now. I asked myself, "Are we truly independent? Do we have that freedom?" For me, national anthems are symbols of freedom: the freedom of independence. So I had an instrumental band come and play the Ugandan anthem, but in reverse, as I performed a poem by Ssebo Lule, a Luganda poet, in front of the audience. The piece was speculating about not having freedom, going to protests, and police officers waiting to arrest me.

GM: What's your next project?

OR: I'm still experimenting with music and verse – I should release an album next year.

Odur Ronald's work is on view atDak’Art – Biennale de l'Art Africain Contemporain from November 7 to December 7, 2024, in Senegal's capital.

Odur Ronald (b. 1992) is a multidisciplinary artist in Kampala. His works engage with the complexities of socialpolitical interactions and their influence on contemporary issues of power, movement, access, belonging, and personhood. Recent exhibitions include the 14th Kaunas Biennale, Lithuania (2023); the 60th Venice Biennale, Uganda pavilion, Italy (2024). Upcoming ones are the Dakar Art Biennale, Senegal (2024), and the Liverpool Biennial (2025). In 2024, he participated in the Gasworks Residency in London.

Giulia Menegale is an independent curator and writer.

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas