“the future is being made now”

18 April 2014

Magazine C& Magazine

11 min read

In December 1993, Nelson Mandela guest-edited the Christmas issue of Vogue’s French edition. In agreeing to work on this special issue, Mandela, whose death on 5 December has prompted a global outpouring of grief, praise and warm remembrance, was following in the footsteps of the Russian-born painter Marc Chagall, Italian film director Frederico …

In December 1993, Nelson Mandela guest-edited the Christmas issue of Vogue’s French edition. In agreeing to work on this special issue, Mandela, whose death on 5 December has prompted a global outpouring of grief, praise and warm remembrance, was following in the footsteps of the Russian-born painter Marc Chagall, Italian film director Frederico Fellini, and Spanish painter Joan Miro, all of whom had previously guest-edited the publication.

The Mandela special issue, which followed on the Dalai Lama’s issue the year before, was conceived by style maven and then editor Colombe Pringle and included 92 pages devoted to Mandela.

Aside from an interview with the future president of a non-racial South Africa, the issue included an overview of his youth, articles on ethnic diversity and initiation rites, as well as a visit to his home in Cape Town. Not known to be timorous in articulating his desires, it was reported at the time that Mandela insisted the issue also include a feature on African wildlife.

Today, most people I mention his editorial accomplishment to express genuine surprise. Few if any though see the relevance of this odd historical quirk to the ongoing controversy around a set of artworks bearing Mandela’s signature.

Briefly, the row concerns the apparently dubious activities of Mandela’s former personal lawyer, Ismail Ayob, and Cape Town businessman Ross Calder. By way of a series of elaborate schemes, the two sought to quantify and then profiteer off Mandela’s legacy.

The earliest scheme, marketed as “Touch of Mandela” to interested buyers, involved a series of sketches of subjects from Robben Island that held “symbolic and emotional value” for Mandela”. Varenka Paschke, the granddaughter of former president PW Botha, one of Mandela’s staunchest enemies, is said to have helped him create the works.

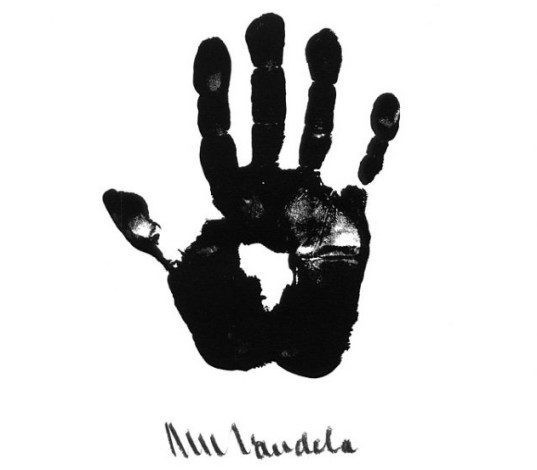

After the scheme’s collapse in 2002, a number of other projects were undertaken, amongst them a portfolio titled Impressions of Mandela, which consisted of ink prints of Mandela’s hand, the outline of the African continent visible in their palm. Oprah Winfrey, David Beckham, Bill Clinton, Samuel Jackson, the Sultan of Oman and Prince Charles are all said to have been buyers, believing that their money was going to charity.

The palm print works especially tested the limits of credulity. This did not dissuade London daily The Times from reprinting one of them on its front page in 2003, an image of a palm print of Mandela’s right-hand, the outline of Africa clearly visible in the middle.

Whether out of respect for Mandela, or disinterest in what was clearly an dubious marketing ploy, no-one publicly remarked on the art works. Then, in October 2002, the Sunday Times ran a cover story about a High Court summons involving Ayob and the liquidators of the advertising agency Concept, who produced the “Touch of Mandela” works. In the article journalist Bonny Schoonakker quoted Martin Feinstein, a director of Concept, as saying the project was as an “outrageous attempt to profiteer from Mandela’s name”.

The day after it appeared Schoonakker received a personal phone call from Mandela and an offer to visit him on a game farm near Lephalale (formerly Ellisras) in Limpopo province. “He was initially very upset about the article and said I had served my journalistic duties dishonourably,” said Schoonakker in an interview in 2005.

After explaining how Ayob had blocked any enquiry into the project, Mandela softened and for three hours spoke about the intricacies of doing people favours, including for Ayob.

“Mandela himself actively endorsed and supported the original attempts to sell him as an artist,” added Schoonakker. “In my interview with him … he emphatically supported and approved Ayob’s and Calder’s outrageous schemes.”

Due to the sensitivity of the issues at stake the Sunday Times never ran the story. In April 2005, the investigative magazine Noseweek revived it with a lead article accusing Ayob and Calder of engineering an elaborate “confidence trick”.

“Right from the start, the project looked highly questionable,” commented artist Sue Williamson in a 2005 editorial published on artthrob.co.za. “Anyone with an art training could see that. There was none of the awkwardness and skewed perspective that would have been apparent in a drawing made on the spot by an older, untrained person like Mandela which would have given the drawings a real interest and sense of authenticity.”

Even respected South African artists like Willie Bester and Marlene Dumas were implicated in the controversy after their participation in an exhibition organised by Calder in Davos, Switzerland, in January 2005. The exhibition was allegedly held without the permission of the Nelson Mandela Foundation (NMF), a non-profit organisation expanding upon the work Mandela has done throughout his life.

Despite the widespread negative publicity generated by the scandal in 2005, lithographs bearing Mandela’s signature now sell for upwards of R150,000 (€10,000). The National Prosecuting Authority of South Africa, acting to secure Mandela’s interest, is currently investigating the companies that were established to manage royalties from the sale of Mandela’s art, reported the Mail & Guardian newspaper in September 2013.

Although unresolved, Mandela’s position on the matter was made clear in 2005 already. He fired his lawyer Ayob and hired Don MacRobert, an intellectual property lawyer and consultant to the firms Edward Nathan and Adams & Adams.

“Mandela has clearly stated no use without permission and, secondly, never any commercial use,” explained MacRobert, who was tasked with cleaning up Mandela’s intellectual property assets on behalf of the NMF. MacRobert was presented with a shambolic situation. The Department of Trade and Industry – unbeknownst to Mandela or his foundation – had been giving people permission to use his name and image. One example cited by MacRobert was the Madiba range of Shwe-shwe fabric produced by Da Gama Textiles, one of the country’s oldest and leading textile producers. The fabric has Mandela’s face printed on it.

“We don’t mind a Kennedy-ised Mandela,” said MacRobert, by way of clarifying the broad principles informing his work for Mandela. “You see Kennedy museums and Kennedy streets all over America and that’s fine. What we are fighting against is the commercial, profit-making side. We don’t want a Disney-fied Mandela.”

According to MacRobert, this expression cuts to the heart of how Mandela would like his legacy to be celebrated. Despite this statement of intent, the NMF is still inundated with requests by entrepreneurs seeking Mandela’s endorsement for everything from special issue pens to Madiba diamonds to books to crèches bearing his name.

“People should remember that Mandela is not the king; he does not have a royal diary with obligations. He’s Mr Mandela, a retired private person.” Opinions here are likely differ. President Barack Obama, speaking in a televised address shortly after Mandela’s death, praised him for his journey from a prisoner to a president, which, he said, “embodied the promise that human beings - and countries - can change for the better”. He also described Mandela as a man who took history in his hands, and bent the arc of the moral universe toward justice.” News anchors and television pundits have been less careful in measuring their words.

“The medium of television has played a big role in constructing Mandela as tata [father],” wrote Sam Raditlhalo, an associate professor of English at the University of South Africa, in a 1999 essay looking at Mandela’s iconic status. “One could almost feel power slipping from FW de Klerk to Mandela in the crucial run up to democratic elections as his solution of compromise and his willingness to do so, which he placed at the fore of his credo as a leader, reached us in our living rooms.”

In a 2005 interview, Raditlhalo expanded on his thoughts. Quoting Mandela’s biographer, Anthony Sampson, he mentioned that Mandela watched his iconic status being formulated around himself while still on Robben Island, quite separately from himself.

“He knew the pitfalls of therefore believing in the myth of himself, aware of the dangers of personality cult, opting for a ‘We’ kind of discursiveness rather than the ‘I’, mindful that he wished to be seen as a regular person, which of course he was not,” said Raditlhalo.

Active politicking during the course of the 1990s however gave momentum to this burgeoning personality cult.

“As he tours Africa to thank leaders for hosting the African National Congress (ANC), he is valorised as an icon of struggle, peace, but most importantly, potential prosperity for Africans. In the collective minds he is both ‘father of the South African nation’, and the bringer of prosperity to the African masses.”

Almost unavoidably, hero worship gives itself over to a sort of deification, history and myth conflated so that Mandela becomes a sort of messianic figure.

Merwelene van der Merwe’s iconic, 1994 election poster image of Mandela illustrates an aspect of this point. When I discussed the image with an advertising executive who worked on the ANC campaign in 2003 for an article that appeared in Eyemagazine

, he told me how Mandela had posed in a variety of dress options, with a focus group determining the final image. Van der Merwe remembered it differently.

“I was approached by an advertising agency to photograph the senior members of the ANC, as well as Madiba,” van der Merwe, a successful advertising photographer, told me in 2004. “They wanted to use the images for a brochure for international fundraising. The brief was basically to take portraits at the ANC headquarters, at Shell House. I photographed most of the top brass on the first day but was eventually told that I wouldn’t be able to photograph Madiba.”

Returning the following day, van der Merwe finally met and photographed South Africa’s future leader. There was little spark at first between photographer and sitter.

“The shoot initially progressed as it would with any executive. I then realised I needed a bit more. For me, when I shoot someone, I have to connect with them, which is very hard – to connect with strangers.” Something happened when she focussed on Mandela’s eyes. “I remember suddenly becoming very emotional, tears just started to come. I remember looking at him with so much admiration, at his fullness, his sparkling character. It was then that I decided to speak Sotho to him.”

Van der Merwe, who had recently returned to South Africa from San Francisco after eight years abroad, grew up on a farm in the Free State and speaks Sotho fluently. “I knew he is Xhosa, but I said in Sotho, ‘I’m so close to you, if I fall by mistake, just catch me’. He slapped my bum and said, ‘I won’t mind darling’. It was amazing how that little thing, me talking Sotho broke everything. I saw his smile and got it.”

Photography, more so than any other medium, has served to firmly fix Mandela’s image in the popular consciousness. Banned from the South African media for much of his 27-year prison sentence, Mandela’s image is now unequivocal, an easy to decipher figurative statement expressing human dignity and the right of canny revolutionaries to a good old age. Fittingly, given the stark absence of his image in the darkest periods of the struggle against apartheid, his face has appeared largely uncaptioned on the majority of South Africa’s newspapers in the wake of his death. No doubt the photographers who made them will each have an illuminating back-story of their encounter, such was the force of Mandela’s company.

I only saw – let alone met – Nelson Mandela once. It was in March 2005, at the inauguration of the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory and Commemoration on Constitution Hill, Johannesburg. “No flash photography!” we were repeatedly instructed. Prison, the quarries, his eyes, went the explanation. Then the big moment. A policeman in blue raincoat helped the wizened old man into his seat while an alert G-man in an expensive suit took possession of his ivory cane. The press cameras mechanically clicked, albeit without a flash. After four warm-up speeches, it was Mandela’s turn to speak.

“The future is being made now,” he said, “which is why as an old man here today I find it hard to retire.” Retire he has, irrevocably. But we still have the pictures, and the stories, enough to fill a library, perhaps one as vast as the “infinite” one imaged by Borges.

Sean O’Toole is a writer and co-editor of "CitySchapes" , a critical journal for urban enquiry. He lives in Cape Town, South Africa.

This is an updated version of a series of articles published in 1995 in the Sunday Times (South Africa), Creative Review (UK) and BBC Focus on Africa (UK).

Read more from

Flowing Affections: Laryssa Machada’s Sensitive Geographies

Kombo Chapfika and Uzoma Orji: What Else Can Technology Be?

Cabo Verde’s Layered Temporalities Emerge in the Work of César Schofield Cardoso

Read more from

“All that it holds. Tout ce qu’elle renferme. Tudo o que ela abarca. Todo lo que ella alberga.”

Darling, this is Switzerland