“My paintings show that there is no such thing as discontinuity in the history of art.”

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar is presenting her latest work as part of the Körnelia-Goldrausch 2013 exhibition, one of the ten partner projects of Berlin Art Week 2013.

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar (*1974, Oran, Algeria; based in Berlin since 2010), graduate of École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts in Paris, will be presenting her latest work as part of the Körnelia-Goldrausch 2013 exhibition, one of the ten partner projects of Berlin Art Week 2013. Sophie Eliot spoke with the artist.

Sophie Eliot: What does the city of Berlin mean to you?

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar: In 1995 I was fortunate to be able to participate in a fine-arts workshop offered by Wannseeforum in Berlin. It was during this stay that I discovered my deep interest in artistic expression and that I decided to give up my biology studies in order to devote myself to painting. Berlin was already a special city then, giving one the feeling of strangeness and freedom. I began exhibiting here in 2004, which brought me back to the city regularly. Unlike in Paris, where painting was considered anachronistic at the time, Berlin’s art scene was open to all media, with painting inhabiting its own rightful place. It was exciting to be in this city, where there is so much to be inspired by and where there are no restrictions.

SE: Before you started painting, you made drawings. It was only in 2010, when you moved to Berlin, that you took up drawing again in the two series Algérie Année 0 (2011-2012) and Topographie de la terreur (2012-2013). Can you tell us more about this?

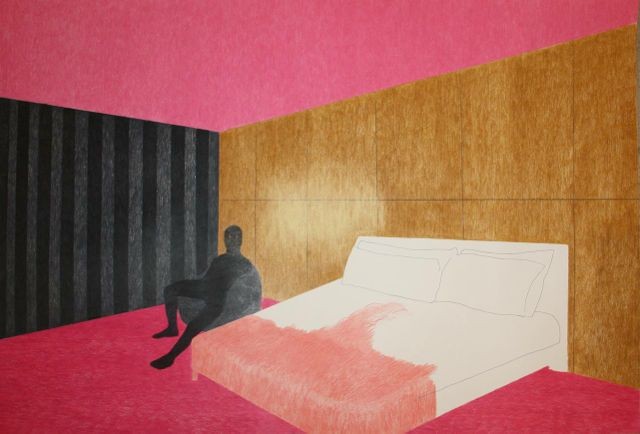

DDB: I would say that I began drawing again simply because I felt free in Berlin to be myself. The Algérie Année 0 series is the product of two concurrent experiences: watching the documentary film Algérie(s) by Thierry Leclère, Malek Bensmaïl, and Patrice Barrat, and living in Berlin, which is a veritable city of memory. The film confronted me with my personal history as an Algerian. I realized that I didn’t own a single book on the history of my country or the Algerian War and the civil war of the 1990s, even though my work has always been concerned with violence. And Berlin is visibly marked by history, revealing the traces of traumatic events such as the genocide of the Jews during the Second World War, or, more recently, the Berlin Wall. It was in Berlin that I encountered the work of artists such as Christian Boltanski, Jochen Gerz, and Gunter Demnig, who have reflected in very interesting ways on memorials and the transmission of memory. Engaging with this led to my project of forty drawings based on archival images from the Algerian War and the civil war. The other series, Topographie de la terreur, was directly inspired by Berlin’s “Topography of Terror,” which is both a documentation center and a permanent exhibition with a particular focus on the rise of Nazism. This series explores the relationship between architecture, interior spaces, and terror. The two series address violence in different contexts. They also express a desire to transform this violence. It was very important for me to create these pieces on the past, but today I am at somewhat of a remove from them. I have returned to focusing on the portrait.

SE: Is that what you are going to show at the Körnelia exhibition?

DDB: For the exhibition I am creating a portrait in the form of an installation made up of different objects: several paintings, two of which are portraits, and a series of small formats of flowers, as well as objects out of wax representing a figurine of a little girl, a pyramid, and a mock-up of an apartment. The portraits are from a series I completed this year entitled Taboo. The title refers to the inhibition I felt during my studies in France to simply paint – and portraits in the classical style at that! As an Algerian, the daughter of Algerian immigrants, I have the feeling that a particular kind of artistic expression is expected of me, in France in any case – that is, video or photography, preferably tackling topics like the ghettos, illegal immigration, or the headscarf. But I situated myself in another discourse from the beginning, appropriating the great subjects of Western painting, such as the portrait, The Women of Algiers by Delacroix, The Bathers, etc. In this way, my paintings show that there is no such thing as discontinuity in the history of art. This history belongs to everyone, to Westerners as well as to those whose parents are from the former colonies. It’s about resituating art in a kind of timelessness that refuses the notion of history as moving in one direction only, as linear; a timelessness that is characteristic of the human, beyond all borders, that transgresses borders both geographic and cultural.*

* See Walter Mignolo’s concept of “border thinking” on the question of the reappropriation and détournement of cultural discourses put in place by the West.

The Körnelia-Goldrausch 2013 exhibition opened on September 20th at Galerie im Körnerpark (Schierker Straße 8, 12051 Berlin) and runs till November 10th, 2013. Opening hours are Tuesday to Sunday from 10 am to 8 pm. For more information, visit www.goldrausch-kuenstlerinnen.de.

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar’s website:www.daliladalleas.com.

Sophie Eliot is a Ph.D. student and art critic based in Berlin. She is currently writing a dissertation on curatorial practices in contemporary African art at the University of Oldenburg, Germany.

English by Millay Hyatt.

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas