Image Interventions in "The African Gaze"

Extending an ongoing conversation around the evolution of image practices in Africa, writer Kim M. Reynolds dives into Amy Sall’s "The African Gaze: Photography, Cinema and Power", and the wider historical context and infrastructure of African image-making practices.

To Correct or Invent (or Both)

Artificial borders and corrupted names were sloppily and irrelevantly constructed in colonized Africa. It didn’t matter that the colonizers couldn’t pronounce “Nkran,” an Akan word for ant, and instead opted for Accra, or that they derived Kenya from “Kirinyaga,” the Kikuyu name for Mount Kenya. The Africa imagined by the colonizers was justified by racist pseudoscience and executed through unimaginable violence. Its legacy persists in our material and imaginative worlds. “For isn’t it odd that the only language I have in which to speak of this crime,” asks Antiguan author Jamaica Kincaid, “is the language of the criminal who committed the crime?”

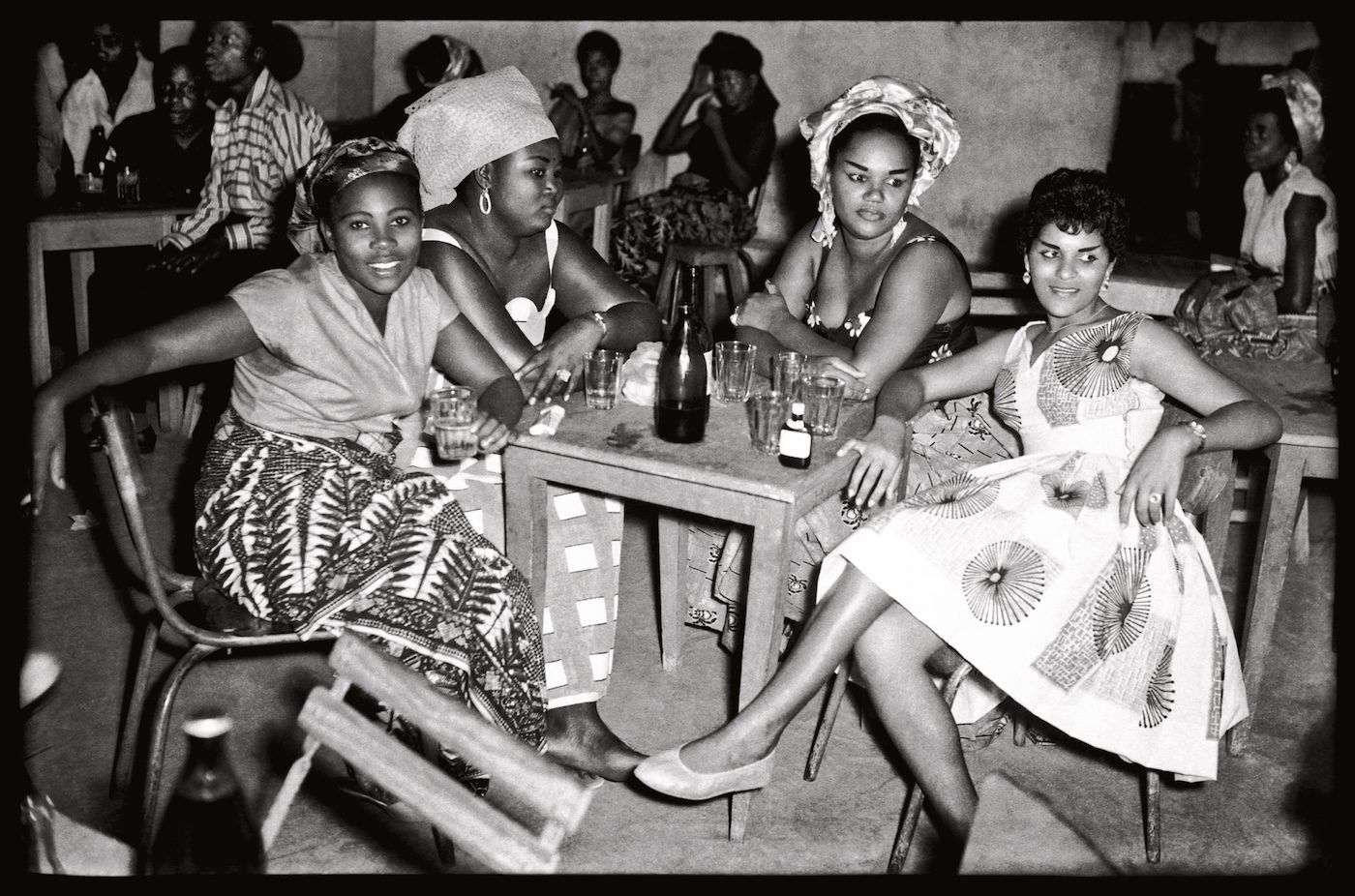

Group of young women seated at a table in a dance hall, Kinshasa, ca. 1950–65. Print Baryta Pigments, 27x40 cm (32x43). © Jean Depara

Amy Sall’s book The African Gaze: Photography, Cinema and Power (2024) responds to this situation by carefully exploring the interplay between sociopolitical histories and African-made imagery through profiles of twenty-five of the continent’s photographers and twenty-five of its cinematographers. The book’s title is a nod to the repositioning of semiotic power as well as to a course Sall taught at The New School titled “The African Gaze: Visual Culture of Postcolonial Africa and the Social Imagination,” which gained popularity beyond the institution.

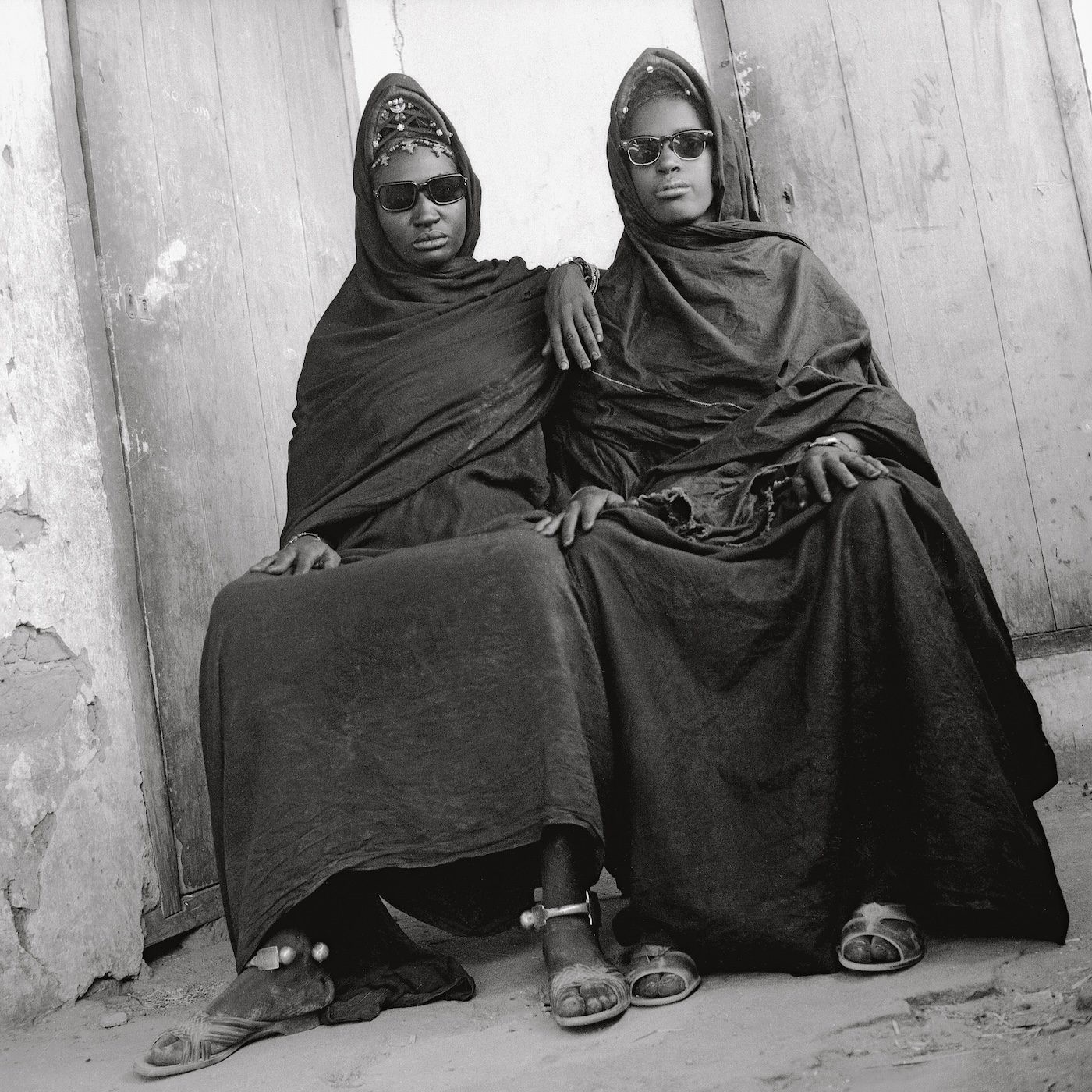

In the West, especially among white practitioners, celebration has been the primary corrective to racist and reductionist tropes, but this can result in an equal depersonalization. Sall divests from this approach into constructing what contributing essayist Mamadou Diouf describes as a “sociology of the infrastructures and institutions” of cinema and photography on the continent of Africa. With stories of the excitement of national independence and the onset of disillusioning neocolonialism, alongside documentation of style and adornment, and the everyday life of various people in various countries, the book gives us readers the opportunity to see ourselves and see for ourselves.

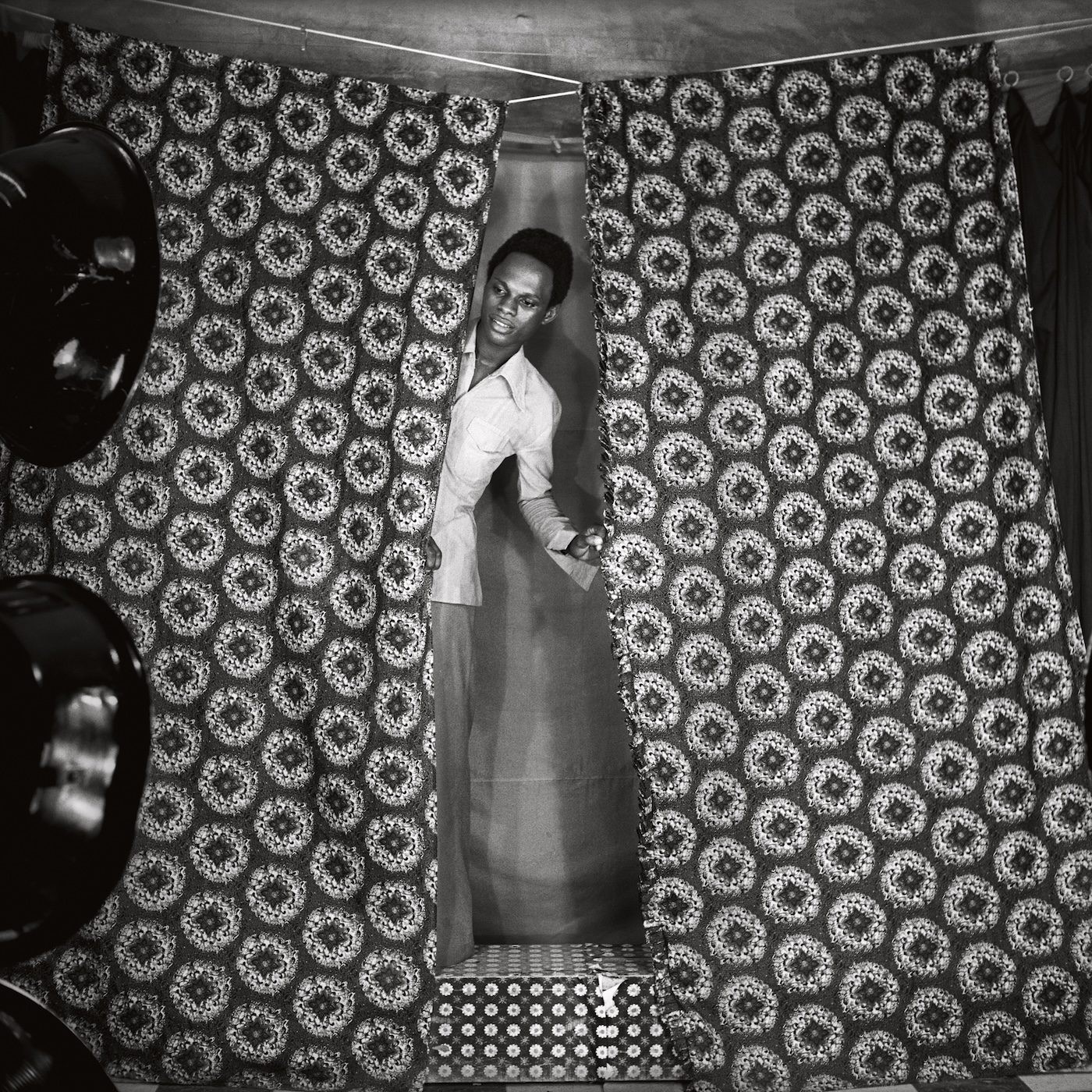

© Oumar Ly. Untitled, Podor, 1963-78.

Cinematic Interventions

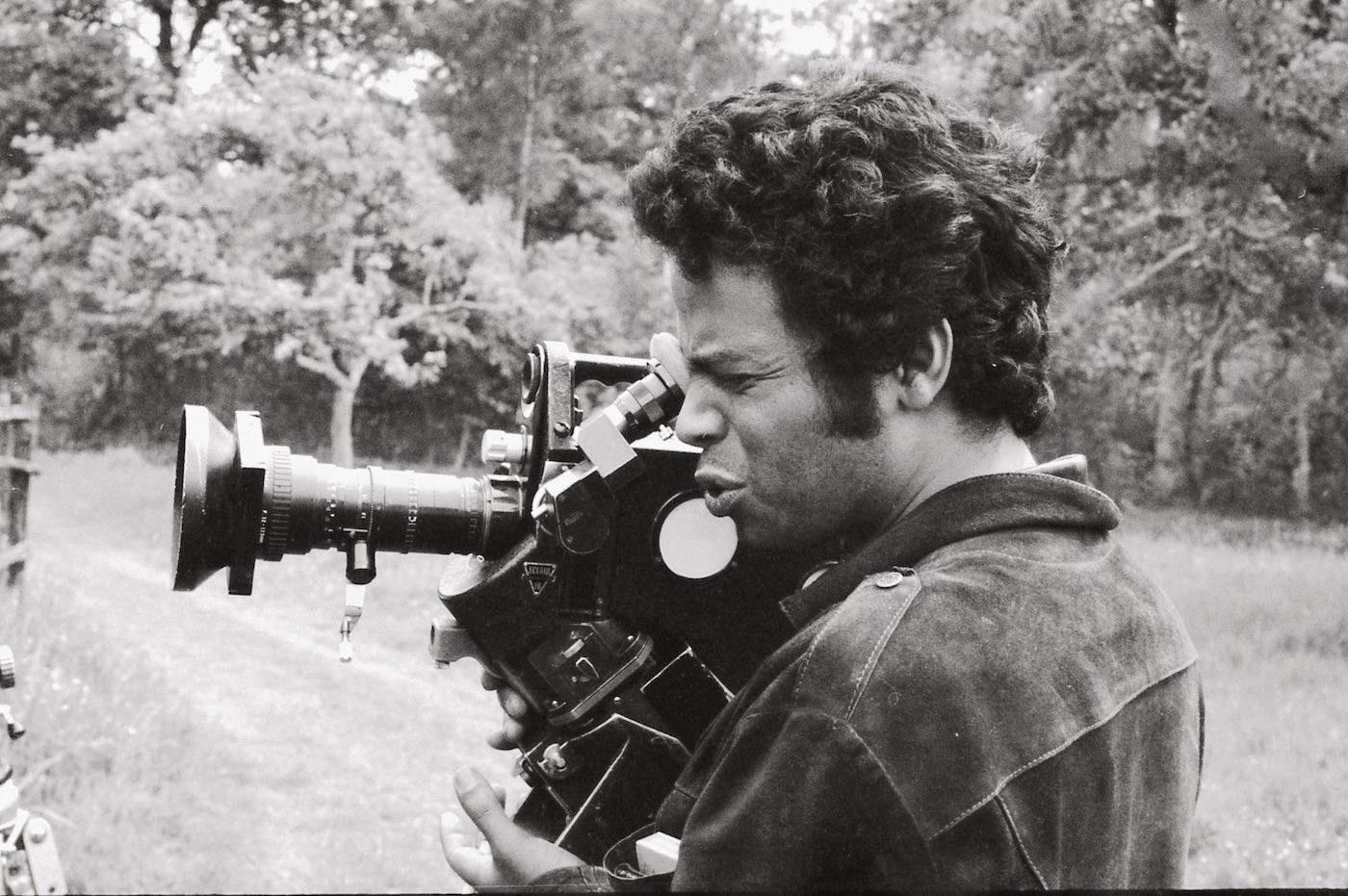

The African Gaze explores the styles, narrative choices, storytelling conventions, and coalitions formed by the artists it profiles, which leads to an examination of their impact and the historical connections they formed across linguistic boundaries. Many of the filmmakers in this collection saw film as a necessary and urgent semiotic tool to fortify national culture during their countries’ nascent independence.

In Senegal, writer and filmmaker Ousmane Sembène devoted his career to portraying worlds and dilemmas that were relevant to his people; he also made the first feature film in Wolof, Mandabi (1968). In Egypt, filmmaker Youssef Chahine portrayed the ongoing Algerian liberation movement through his film Jamila, the Algerian (1958), a fictionalization of the story of liberation activist Djamila Bouhired who played a major role in the movement. Paulin Soumanou Vieyra of Senegal was a major proponent of African cinema as a filmmaker, critic, and builder of infrastructure, working in Senegal and beyond with the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI). Artists like Med Hondo and Djibril Diop Mambéty made satirical and experimental films that explored the disillusionment of leaving home for the metropole only to experience even more dispossession. They denounced the abuse of power of both their current governments and their former colonizers.

Artists have also often taken to film to visibilize everyday people and cultural traditions that provide clues about a bigger story. In Burkina Faso, Fanta Régina Nacro – one of the few women featured in the book, as Sall acknowledges – makes work that explores delicate topics such as the dysfunctional intimacy between men and women. Almost all these films involved contention. Debates emerged over the purpose of film, often hashed out at various conventions among African and diasporic artists, sparking ongoing dialogues. A central question: should films be made for commercial success and influence, or for local recognition in mother tongues?

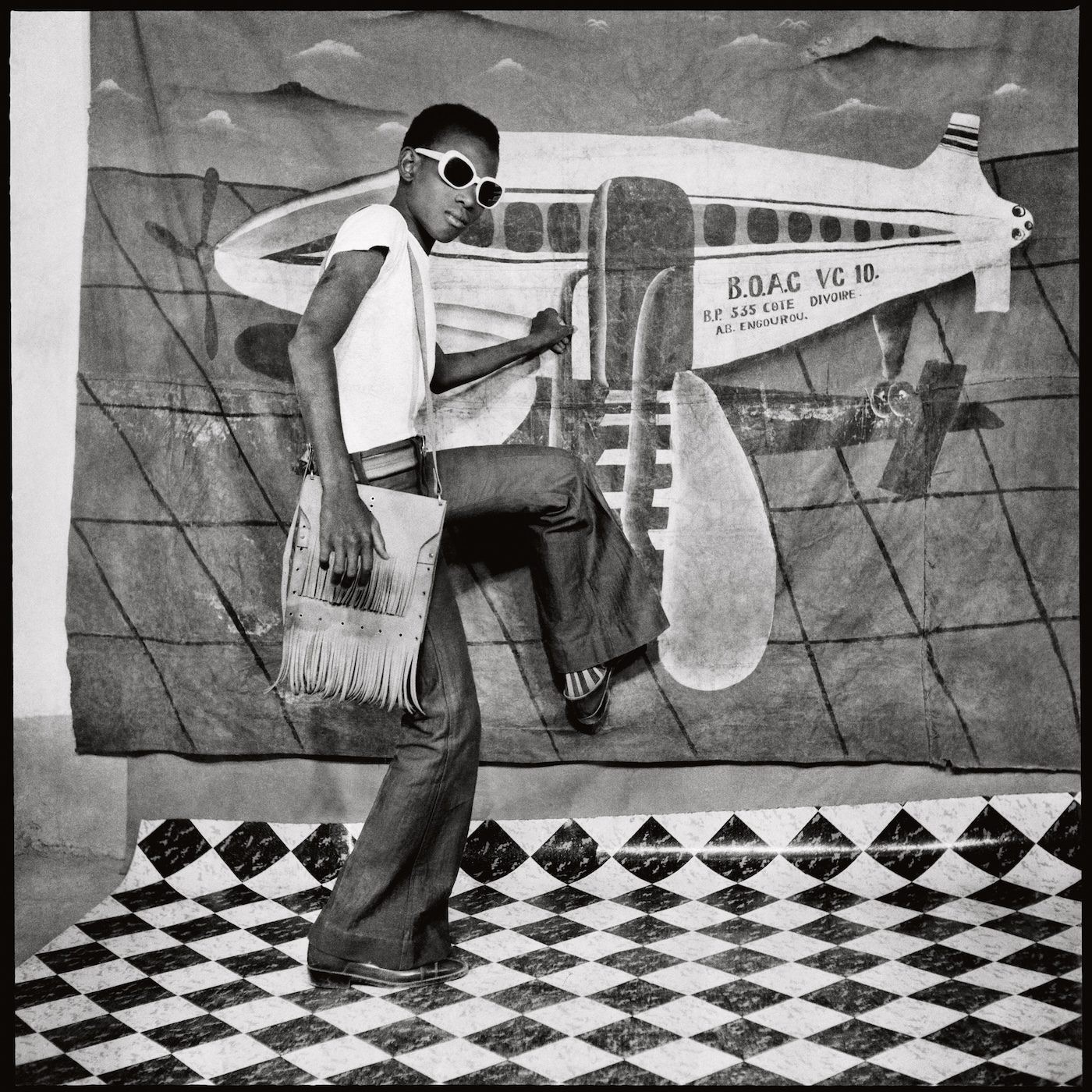

© Sanlé Sory. Je vais décoller, 1977.

Images Across Borders

With the realm of still images, The African Gaze features photographers like James Barnor of Ghana, Mountaga Dembélé of Mali, Ernest Cole of South Africa, Jean Depara of Congo, among others. Barnor pictured an evolving post-independence Ghana, while Dembélé styled Malian studio portraits and mentored fellow Malian artist Seydou Keïta. In South Africa Ernest Cole’s impactful collection House of Bondage (1967) unflinchingly documented the conditions that urban and rural Black South Africans were subjected to under Apartheid. Depara captured the style of people in what was then Leopoldville, now Kinshasa, from music and dance scenes to subcultures such as gangs of young people, US-inspired cowboy-attired collectives, and bodybuilders – “the nuances of Congolese society,” as Sall puts it.

As they persistently created new work, many of these artists’ lives were or are characterized by movement, both voluntary and involuntary. Adama Kouyaté, born in Mali, moved around West Africa and set up a studio in every place he lived, forming a kind of portraiture map of the region. Samuel Fosso, who often plays the leading role in his own photographs, has also belonged to many homes. In one of two artist interviews included in the book, Fosso says: “Nigeria is my mother; Cameroon is my father; CAR (Central African Republic) gave me knowledge” – and all three gave him life.

© Samuel Fosso. Self-portrait, from 70’s Lifestyle series, 1975-78.

Meeting Points

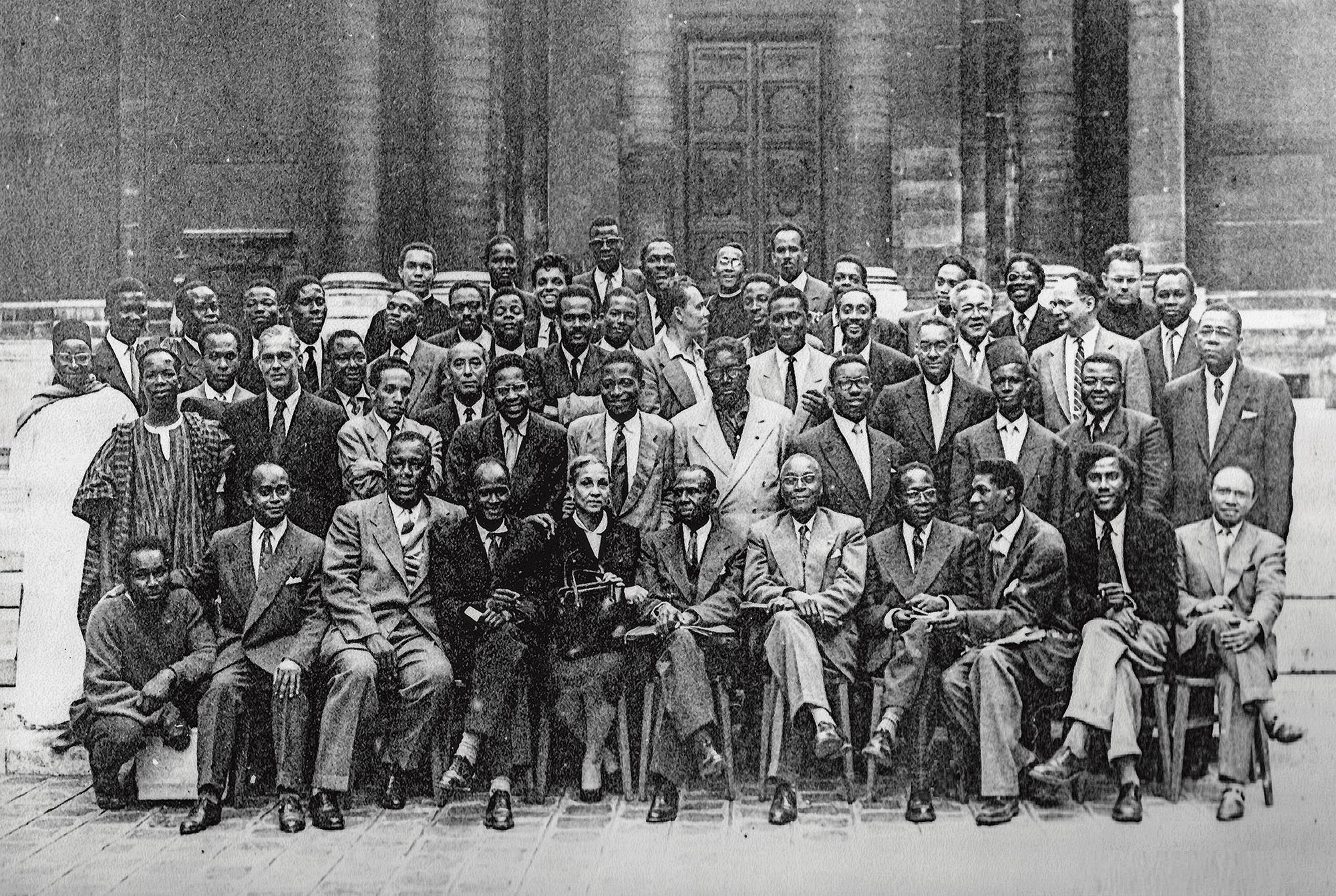

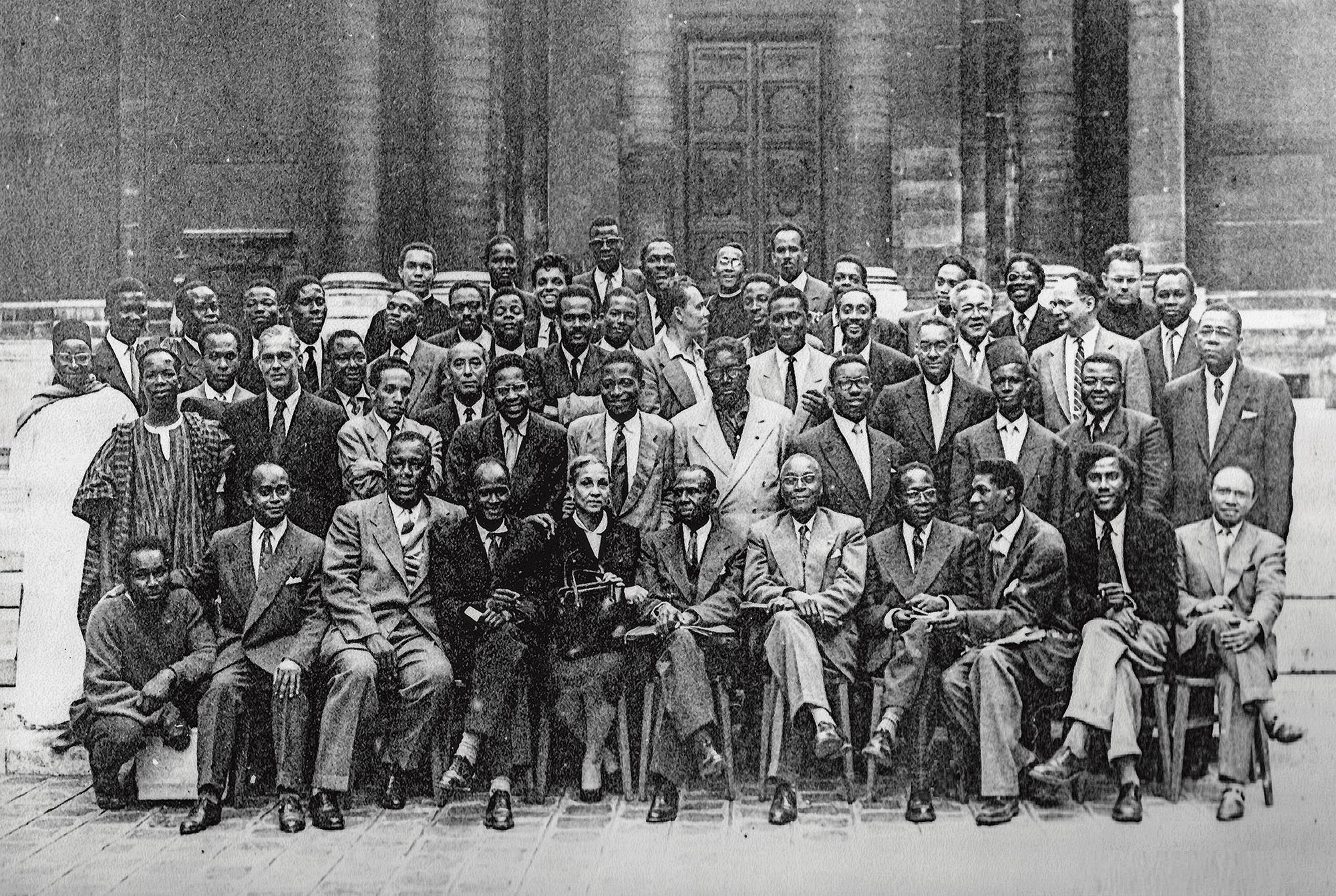

An understanding of a series of conventions, organizations, and mentorship relationships begins to emerge through these fifty artist profiles. They tell a second story of (re)connection between the cohorts who convened at historic gatherings like the reoccurring Pan-African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou (FESPACO) as well as the Second Congress of Negro Writers and Artists in Rome, 1959, and perhaps best-known, FESTAC ‘77, the Second World African Festival of Arts and Culture in Lagos in 1977.

Film and photography animate history as much they tell us who, what, where, and why. They augment our understanding of our societies and in some cases give us an opportunity to look upon pasts thought to be forgotten. The African Gaze reckons with the abstraction and poetics that distinguish historical documentation from art. It seeks to acknowledge the power dynamics at hand, diligently archiving and weaving together the works of African artists in a mission that doesn’t seek to speak back. It simply is because they are.

Kim M Reynolds is a writer, critical media scholar, and tech researcher from Ohio in the US, based in Cape Town. Her work focuses on overlapping contemporary social justice and arts histories on the continent of Africa and the Diaspora. Reynolds is currently co-lead of US-based research and organizing collective Our Data Bodies.

About the author

Kim M. Reynolds

Kim M Reynolds is a writer, critical media scholar, and tech researcher from Ohio in the US, based in Cape Town. Her work focuses on overlapping contemporary social justice and arts histories on the continent of Africa and the Diaspora. Reynolds is currently co-lead of US-based research and organizing collective Our Data Bodies.

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission