Bring the Pain!

In cartooning his forthrightly racist sixth-grade teacher, Oliver Harrington (1912 – 1995) found a practical way to cope with disturbing situations at a very early stage in his life. His ability would not only become his valve, but a method to analyze the madness African Americans had to face every day under the harsh race …

In cartooning his forthrightly racist sixth-grade teacher, Oliver Harrington (1912 – 1995) found a practical way to cope with disturbing situations at a very early stage in his life. His ability would not only become his valve, but a method to analyze the madness African Americans had to face every day under the harsh race politics of the US government.

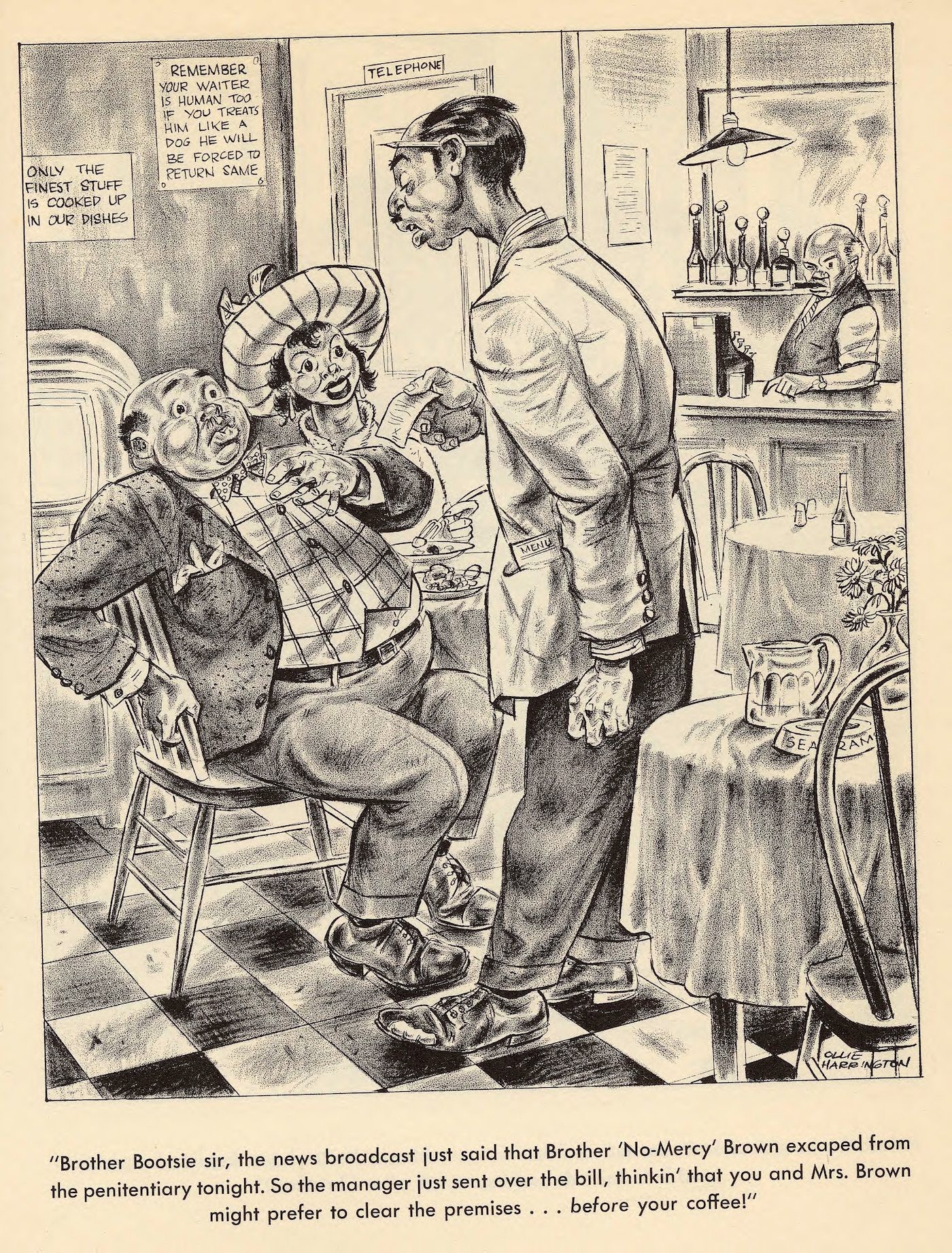

Concurrent to Harrington’s eagerness to challenge stereotypical depictions of African Americans, he understood how to unveil and criticize political mechanisms and their subtexts. With the support of the Negro weeklies, Harrington found a space to evolve his skills, devoid of fear from white censorship. He also gained great acceptance among Black readership because he not only illustrated the malfunctioning political system, but knew how to situate the Black experience within it. Already a trenchant political critic then, he became the first internationally well-known African American cartoonist in 1935 or 1936 (sources vary), when he originated the character Brother Bootsie in his Dark Laughter cartoon series for the New York Amsterdam News. While Brother Bootsie was an explicit protest against Jim Crow racism, Harrington’s cartoons more generally created a space to visualize the mundane struggles of African Americans during the Depression.

Oliver Wendell Harrington was born in Valhalla, New York in 1912 and raised in the Bronx, where he attended DeWitt High School. After graduating from the National Academy of Design, he continued studying from 1936 to 1940 at Yale University, obtaining a bachelor of fine arts. He had already made his debut in the Pittsburgh Courier in 1933, and by this time he was well-versed in cartooning and publishing work in Black newspapers on a regular basis.

With the outbreak of World War II, Harrington was sent to Europe and North Africa to work as a war correspondent for the Pittsburgh Courier. During that time he published Jive Gray, an adventures comic about an African American aviator. In documenting the experiences of African American soldiers abroad, his visual style changed and sharpened his criticism, focused at that time on the hypocrisy of US society as it sought to combat fascism abroad while maintaining segregation politics at home.

<figcaption> Oliver Harrington, Bootsie and Others, date unknown. Ink. Courtesy of Dr. Helma Harrington; The Ohio State University, Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum.

After the war, Harrington worked for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Unafraid to speak his mind publicly, he criticized the US government’s treatment of Black veterans and was instantaneously labelled a communist. Yet Harrington’s statements about Black lives in the States all converged when he uttered his strong belief that there was nationwide apathy about legislation against lynching.

Concerned Harrington could lose his passport and suffer other repercussions, a Black friend in military intelligence warned him that he was under FBI investigation. Harrington moved to Paris, where he continued writing for various US periodicals and was associated with other Black US expatriates. Shaken by his close friend Richard Wright’s death in 1960, Harrington was convinced that he had been murdered by the CIA.

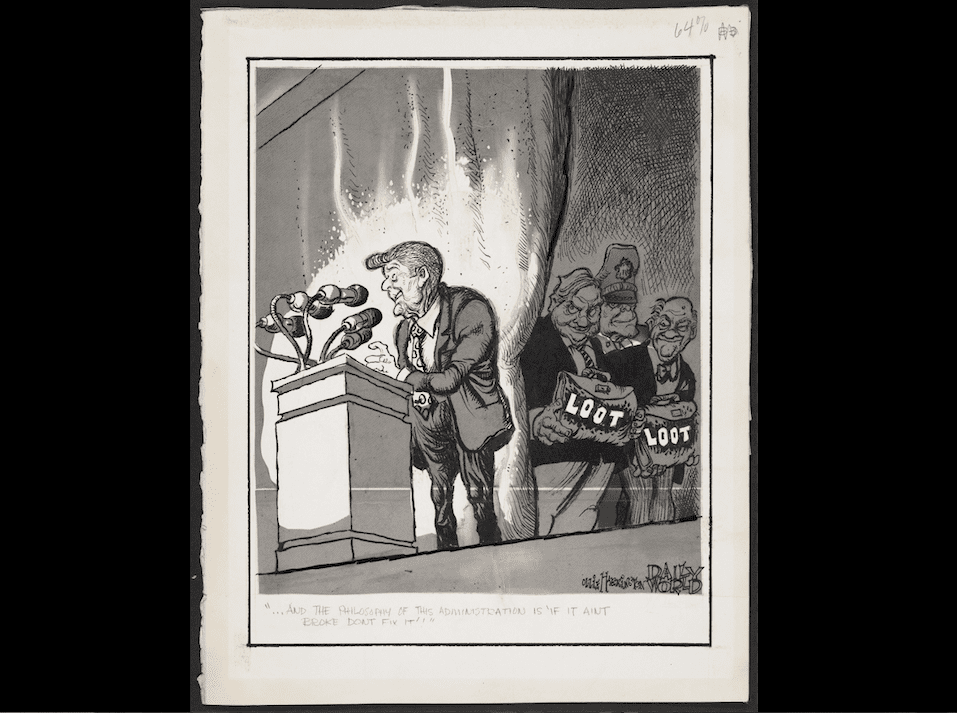

After spending several years as an expatriate in Paris, in 1961 Harrington accepted a job to illustrate a series of American classics for the Aufbau Press, an East German publishing house in Berlin. Though he didn’t intend to stay long, Harrington moved to East Berlin, where he lived and worked until his death in 1995. He created hundreds of cartoons dealing with themes like racism, apartheid, the Vietnam War, the arms race, social injustice, and fascist dictatorships in Latin America, but never featured any topics related to the German Democratic Republic. Despite this he created cartoons and illustrations for German newspapers like Eulenspiegeland Das Magazin.

To stay updated about US politics, Harrington and his wife subscribed to various US periodicals, and he even went to West Berlin to buy copies. When he applied for a press pass as a foreign correspondent for the Daily Mail toward the end of the 1960s, however, he became suspicious to the GDR government. Harrington had been spied on by the FBI in the States from 1946, in France foreigners were often watched by the Deuxième Bureau, and now in East Germany he was being watched by the Stasi.

Though Harrington lived hundreds of miles away from the US, he never gave up the struggle for Black liberation. Despite being physically apart from his community, he always drew for an African American audience. Today his forgotten work reveals itself as a documentation of Black perceptions and struggles of his time. More than that, it is a manifestation of how African Americans created their own spaces in order to communicate and resist power structures, and enable themselves to own the pain imposed upon them.

Mearg Negusse is based in Frankfurt am Main where she currently studies art history.

This text was initially published in the second C& Special Edition #Detroit and commissioned within the framework of the project “Show me your Shelves”, which is funded by and is part of the yearlong campaign “Wunderbar Together (“Deutschlandjahr USA”/The Year of German-American Friendship) by the German Foreign Office. Read the full magazinhere.

Feature

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Feature

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025