Brandon Gercara: “I have the impression of being in a permanent state of displacement”

8 December 2022

Magazine C&

Words Syham Weigant

6 min read

For the Casablanca Biennale, the artist explores feminist propositions as a tool for achieving emancipation and better ways of living together.

Contemporary And: The artistic apparatus you have planned for the BIC makes use of a particular technique (lip sync) and scenography (pallet wood). Can you explain your choice of media?

Brandon Gercara: I was inspired by the practice of drag queens. Lip sync is a playback technique, designed to make it look like the lips are synchronized with the words. The “Lip sync de la pensée” project reanimates the discourse of researchers working at the interface of feminist studies and decoloniality: people like Asma Lamrabet, Françoise Vergès, and Elsa Dorlin. The practice of lip syncing is accompanied by a total embodiment of the person in question, via clothing, hairdo, and even facial expressions and gestures. The theatrical form enables a rethinking of the power of evocation by fostering direct transmission in front of the audience. “Lip sync de la pensée” is a straightforward tool for shining light on a plurality of ideas.

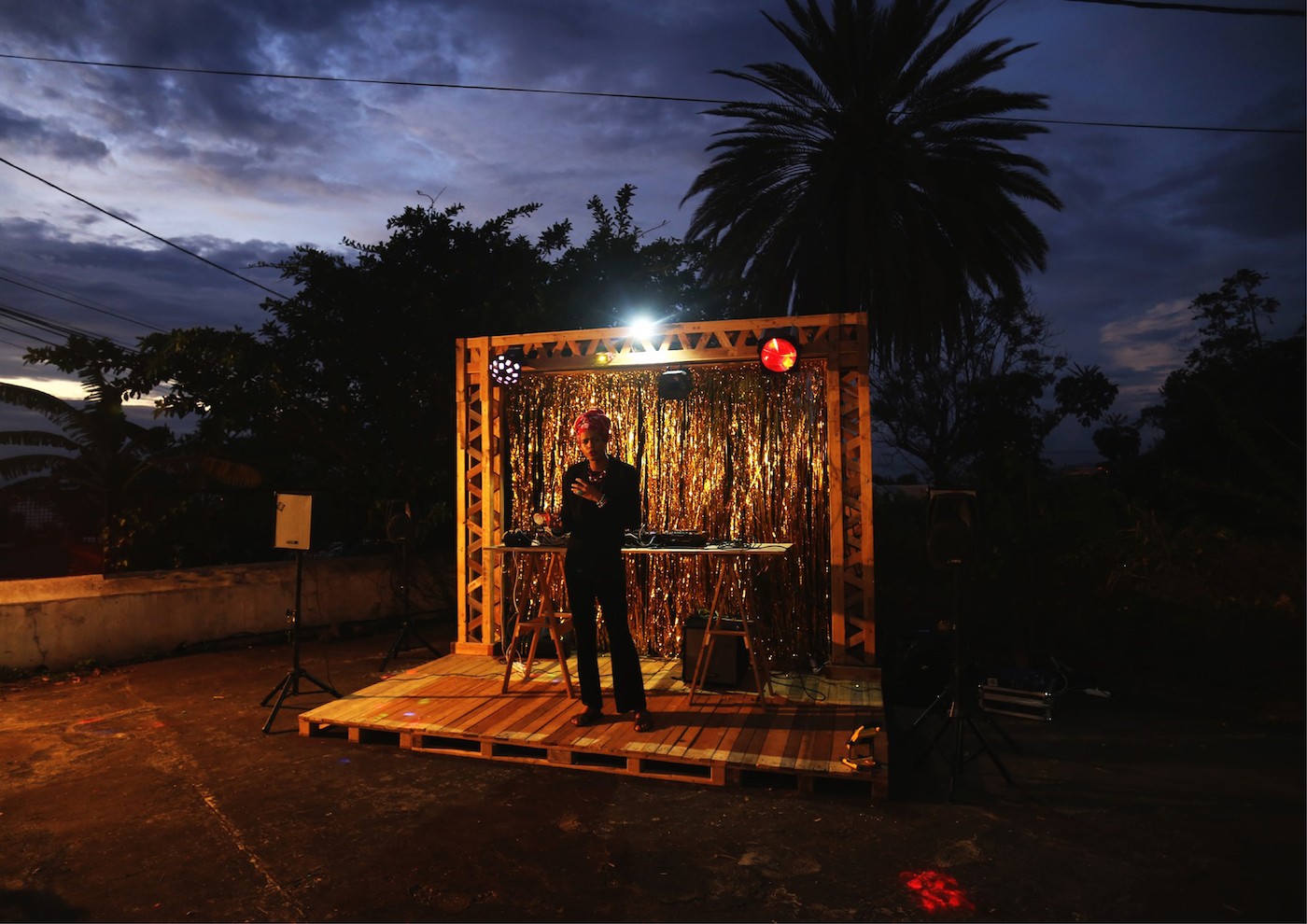

<figcaption> Brandon Gercara, Lip sync of thought. Installation view at Biennale Internationale de Casablanca, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

In the work I do in the visual arts, I use imitation as a tool, just like the pallet-wood scenery, which mimics traditional sets. It echoes the temporary platforms and piled-up pallets you find at demonstrations. It’s a material that’s easily available and can be used in a pinch. It’s also about deflecting the main function of the pallet—which is to transport goods—and redeploying it as a support for the traffic of thoughts and ideas.

For the biennale, I chose to play a video recording shot by the sea in Réunion. The sea is the main way of accessing the island, and it is loaded with colonial and capitalist history and narratives. Like a washed-up pallet, it’s a matter of asking questions about the way ideas navigate from one territory to another and about what that produces or deconstructs.

<figcaption> Brandon Gercara, Lip sync of thought. Installation view at Biennale Internationale de Casablanca, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

C&: You have been involved for some time in African biennales staged by Muslim countries (Mali, Morocco). Has that had an influence on your practice?

BG: Although the island I come from is dominated by Catholicism, the Muslim religion has a place in our culture. And beyond that, the identities that are constructed on the African continent have a similar composition to Réunionese identities, so I am not a complete fish out of water. On the other hand, when I arrive in Mali, for instance, I am aware of the privilege I have as a tourist. I am a white person in Bamako. These are tie-ins that ask questions of my art: how does the process of racialization vary from territory to territory?

The Casablanca biennale was a chance for me to take a closer interest in Islamic feminism based on the content of Asma Lamrabet’s work. The idea I proposed for my performance was fleshed out to enable me to explore the diversity of feminism and its different models. However, the legal aspect is a challenge to me, particularly in Morocco: the law does not protect people who are LGBTQI+. Worse, it “encourages lynchings,” in the words of Abdallah Taïa. I don’t know how people will view my research work but my sense of adelphity pushes me to present it.

<figcaption> Brandon Gercara, Lip sync of thought. Installation view at Biennale Internationale de Casablanca, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

C&: What does the concept of diaspora mean for you? Is it something you apply to yourself?

BG: Classically speaking, the word diaspora relates to the dispersion of a community throughout the world. For my part, I have the impression of being in a permanent state of displacement. To provide a frame of reference here, the island was by and large settled in the context of the Black slave trade: the commercialization of enslaved people forcibly shipped to Réunion by French colonists. To start with, most of these people were from Madagascar and Southeast Africa as well as from Comoros and Mayotte: they had been brought in to work the land for coffee, spices, and sugar cane.

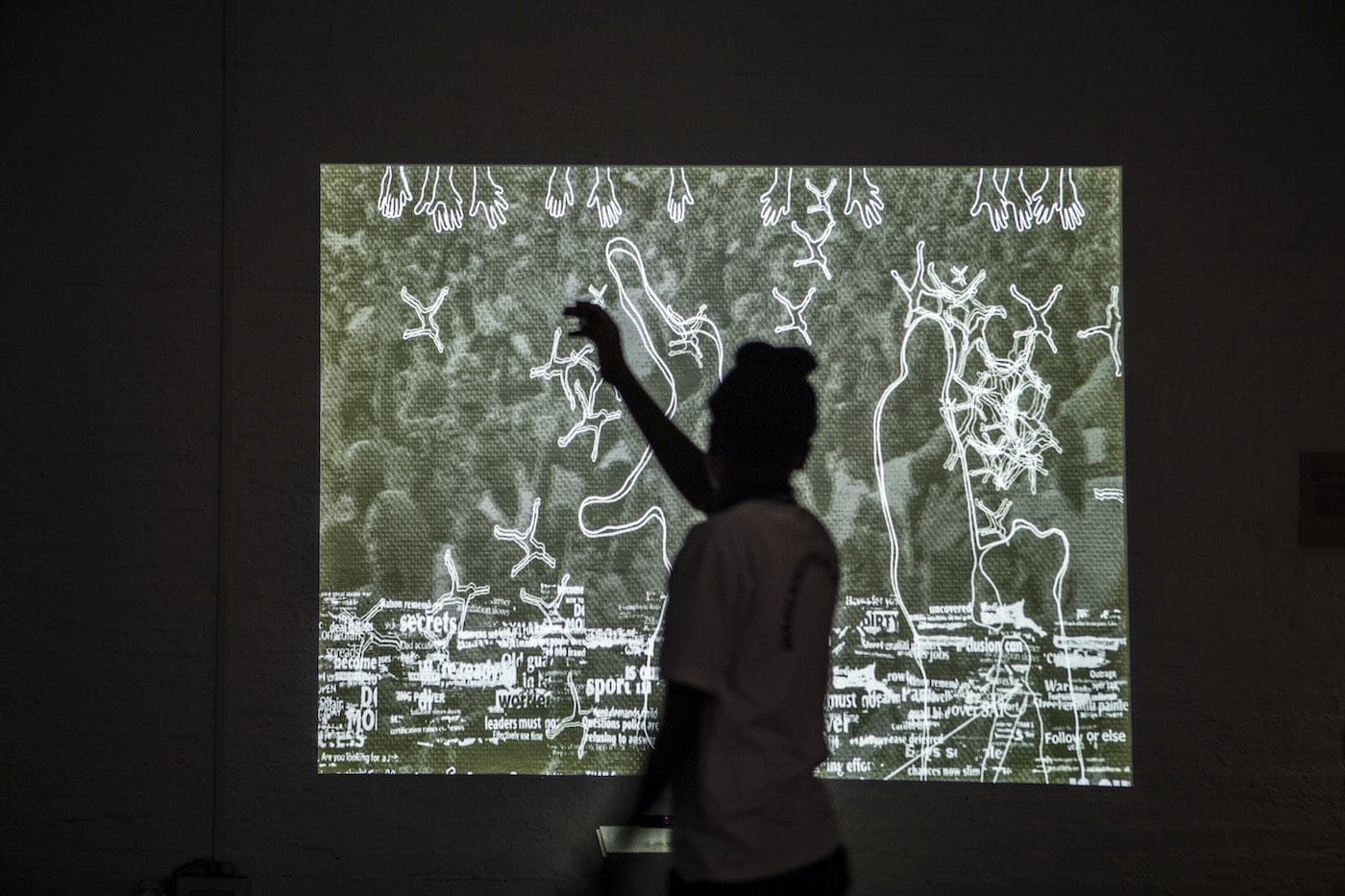

<figcaption> Brandon Gercara, Lip sync of thought, performance/installation, speeches by Asma Lamrabet, Françoise Vergès, Elsa Dorlin, FRAC REUNION Collection, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

The period of engagisme (indentured labor) saw the arrival of Indian Tamils (Malbars), who were to carry on farming these resources as the workforce of the former slave owners. The Muslim Indians (Zarabs) and the Chinese did well out of the trade. After departmentalization, the population of the island was primarily bolstered by state functionaries—French nationals from Metropolitan France (Zoreys). The makeup of the different social and economic legacies here is the result of these movements of people. The displacements continued when Réunionese families had their property expropriated to promote the gentrification of “tourist” zones; this was accompanied by a politics of “The future is elsewhere, and definitely not in Réunion,” even as new Zoreys settled there.

As regards the LGBTQI+ diaspora, LGBTQI-phobic oppression and the lack of space and visibility for the community force people to leave the island, typically to go to France—this applies to the most privileged. And we shouldn’t forget all the LGBTQI+ people who are excluded by their families.

<figcaption> Brandon Gercara, Lip sync of thought, performance/installation, speeches by Asma Lamrabet, Françoise Vergès, Elsa Dorlin, FRAC REUNION Collection, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

C&: What does being an artist mean for you?

BG: It seems to me that the figure of the contemporary visual artist has been blurred by the West and the art schools there. From the experience I had as an art student on Réunion, I realized that as an artist you have to have your references validated by institutions, totally exogenous references. I often feel like you have to make yourself white if you want to stake a claim as a visual artist—it seems like my culture would have to be excluded from my practice.

But who has the authority to approve the position of a visual artist? And is this validation necessary? I don’t think there’s any universal definition—rather, it varies from culture to culture.

To my mind, a visual artist is someone who works in the plastic arts, who offers a way of looking, an experience.

The5th International Biennale of Casablanca takes place in two stages, with exhibitions and events from 17 November to 17 December 2022 and from 9 February to 11 March 2023.

Brandon Gercara is a visual artist/researcher, a decolonial activist, a non-binary, gay, queer, French/Creole Réunionese, and an animist.

Syham Weigant is an art critic from Morocco.

from

In Conversation

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

‘To Treat Process with Care and Intention’: Favour Ritaro Carries Forward Important Curatorial Legacies

from

Identity

Kombo Chapfika and Uzoma Orji: What Else Can Technology Be?

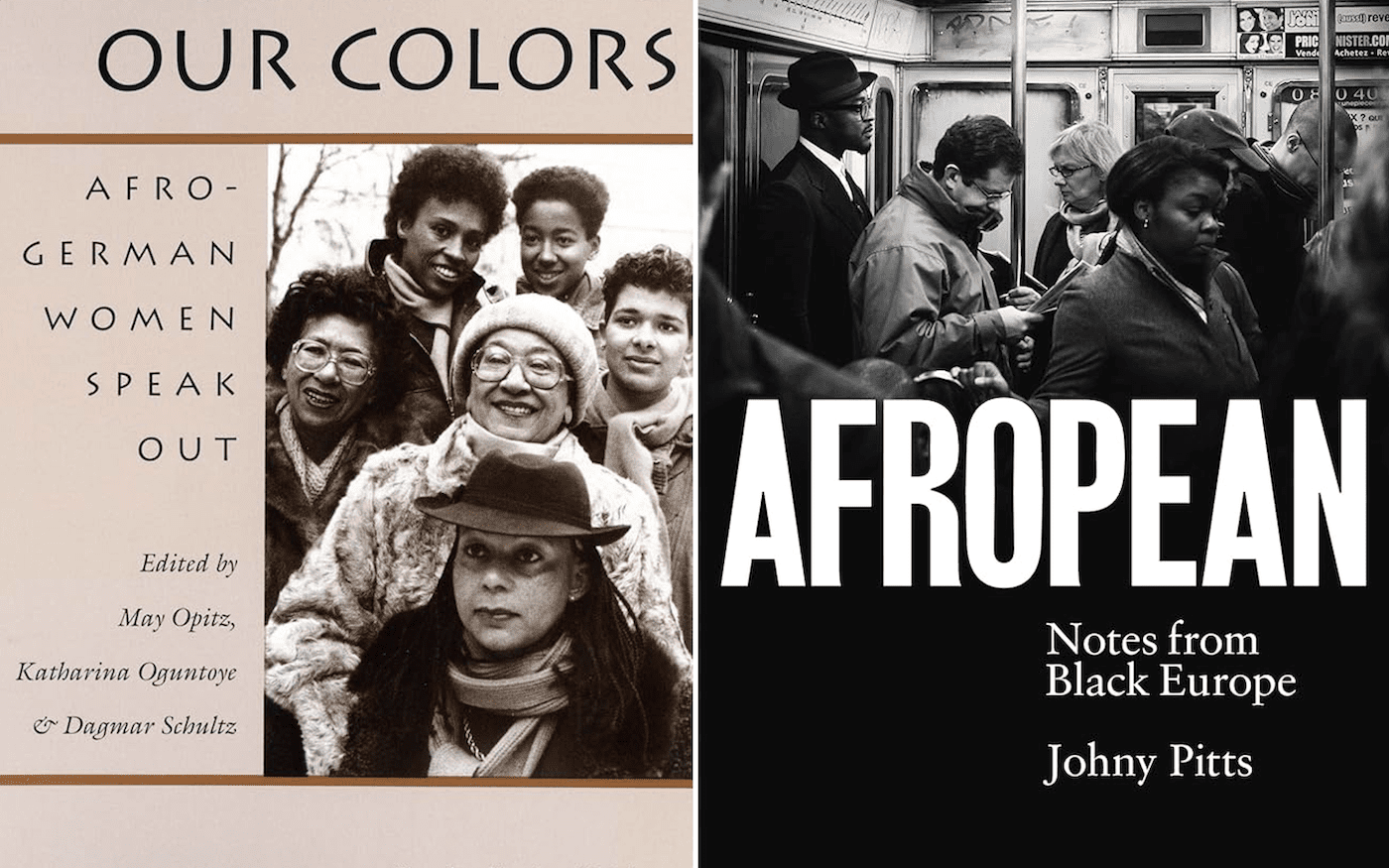

Thinkers and Titles: On Black German Literary Tradition