Àsìkò Diaries

In the series Curriculum of Connections, we bring together critical voices, ideas, and projects working towards educational, artistic, and research practices. In this space, we learn, unlearn, and co-investigate old and new territories of knowledge systems, collaborations, and imagination. Àsìkò, an alternative art school, is the brainchild of Bisi Silva, the Founding Director of the …

In the series Curriculum of Connections, we bring together critical voices, ideas, and projects working towards educational, artistic, and research practices. In this space, we learn, unlearn, and co-investigate old and new territories of knowledge systems, collaborations, and imagination.

Àsìkò, an alternative art school, is the brainchild ofBisi Silva, the Founding Director of the Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (CCA, Lagos). Initiated as a curatorial and experimental platform,Àsìkò operated from 2010-2016 and bridged many gaps found in art educational programs across the continent. With Lagos as its home base, the program traveled to Accra, Dakar, Maputo and Addis Ababa and invited lecturers from around the world to critically engage with emerging curators, artists and cultural producers from the continent. In speaking with three artists about their Àsìkò experience, we recognize the importance of the program’s discourse and legacy.

Mimi Cherono Ng’ok is a visual artist based in Nairobi and works predominantly in photography. She was a participant of Àsìkò Accra 2013 – The Archive: Static, Embodied, Practiced and a facilitator of Àsìkò Maputo 2015 – A History of Contemporary Art Mozambique. Victoria Udondian is an interdisciplinary artist from Nigeria who trained as a tailor and fashion designer and has recently received an MFA in Sculpture. Udondian was a participant in Àsìkò Accra 2013. Lastly, Dana Whabira is a research-based spatial artist with a background in architecture who participated in Àsìkò Dakar 2014 – A History of Contemporary Art in Senegal and is now representing Zimbabwe at the 57th Venice Biennale.

Stephanie Baptist: What was it like to interact and learn with the same group of individuals over five weeks?

Victoria Udondian: Àsìkò was challenging and interesting. It was an intense five-week program and a rare opportunity to be among peers from different parts of the continent. The pedagogical model of the program was also a way to familiarize ourselves with what graduate school would be like, especially given some of the seminar sessions and texts we were engaging with. I didn’t read a lot of this material in my undergraduate studies in Nigeria. It was great to have so much discourse in contemporary art practices on global and individual scales. Most artists came from different stages of their careers so it was fascinating to be with those people. Everyone was going through a mutual learning process, and all these different experiences being brought to the table were invaluable for me. The facilitators also had different backgrounds, which was very illuminating. We had a seminar on the archive from facilitators from different parts of the world, who were engaging and critical on many levels. This was also beneficial, beyond being amongst my peers.

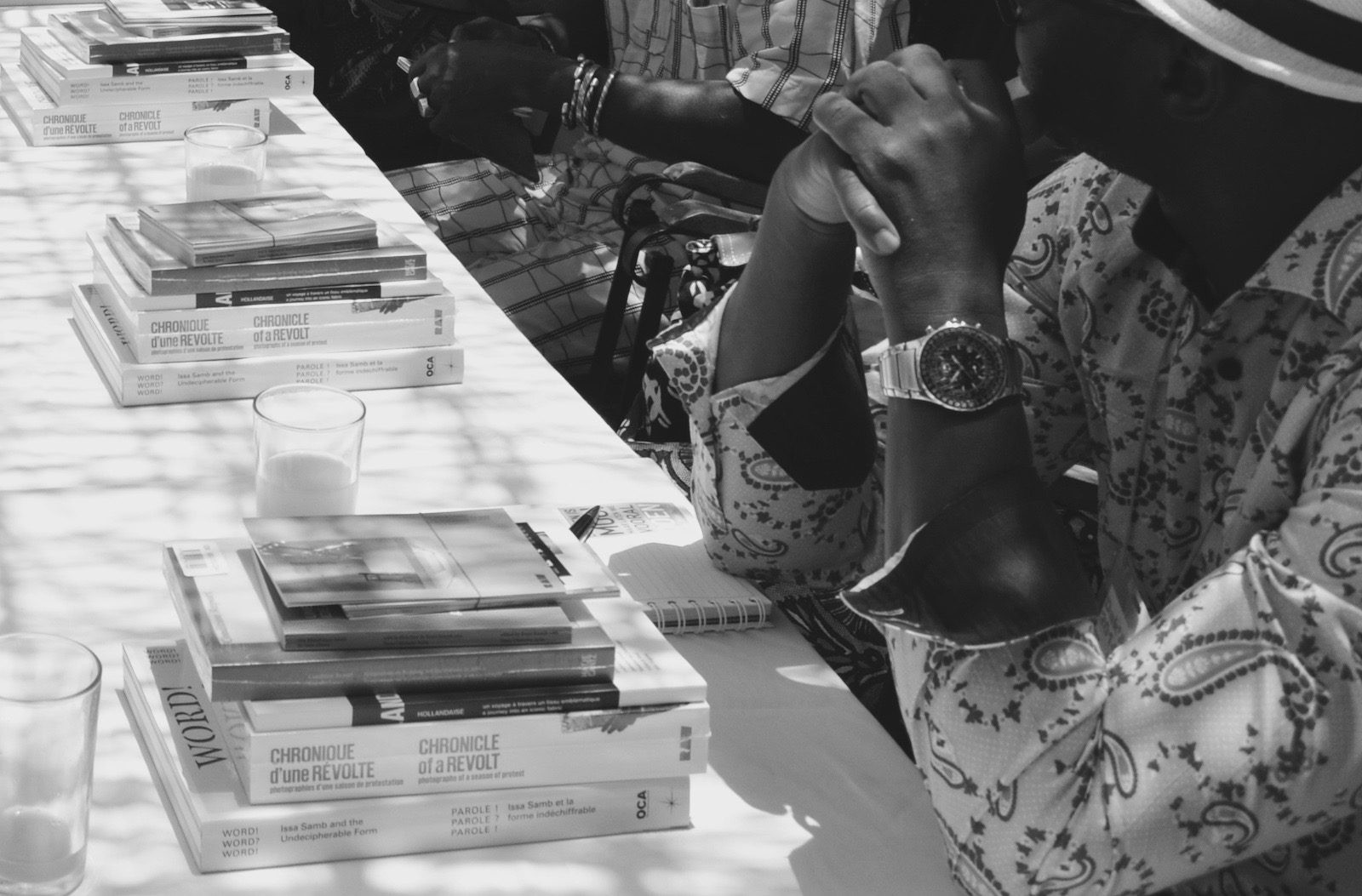

Participants of Àsìkò Art School 2014. Courtesy of Erin Rice.

Mimi Cherono Ng’ok: It was interesting. I think I learned the most when I was in Accra. There were certain things I took for granted. Because of art school, I had already experienced the format for readings that facilitators utilized. In Accra, I got to understand that not everyone felt comfortable reading texts as part of visual discourse and speaking about them. One of my roommates started a reading group for all of us to discuss the assigned texts before going to seminars. It helped me understand other people’s perspectives better and realize that not everyone started with the same references as me or was as comfortable engaging. I made so many valuable friendships in those five weeks. It was intensive and challenging, but worth it.

Dana Whabira: At Àsìkò, we got to meet and work with artists based in countries all over the continent. I see Àsìkò as a Pan-Africanist concept in this sense, and I got to experience firsthand the program’s ability to close any physical, geographical, and intellectual distances between us. Naturally, there were many similarities and differences between us as individuals, but I was also able to learn from them. The ties between myself and many of the individuals that I met at Àsìkò go beyond just the five weeks of the program; the conversations have extended and developed into future projects. The human connection is often overlooked when assessing educational courses and networks. I find that I made lifelong friendships at Àsìkò. I was fortunate to meet Igo Diarra, Director of Galerie Medina in Bamako, who invited Njelele Art Station to cooperate on the Symposium d’Art au Mali (SAM), which took place as part of the Recontres Bamako 2015 program. That forged a collaborative working partnership between these two spaces. Language was quite a challenge in Dakar. Igo became pivotal not only in connecting us as arts professionals but also in assisting with our navigation of the city and its rich cultural heritage.

SB:Mimi,can you tell me a bit about your experience as a resident in 2013 and then as a facilitator in 2015?

MCN: I that felt being a participant was easier. There is more emotional labor involved as a facilitator. When you show facilitators your work, it is a lot for them to interact and engage. It is intensive, as you’re doing it for ten to twelve people. I appreciate what facilitators bring to the process. As a participant, I was able to focus on myself. As a facilitator, my role was much bigger than my own work, as I had to meet residents where they were. I was interacting critically with other people who were just learning and didn’t yet have the language to present their work. I learned a lot from other facilitators in the program how to do this. In art school, I had very hard critiques, so I thought that is how it should be. You have so many critiques that you get used to the methodology and you learn how to respond and discuss. However, interacting with fellow facilitators Nontsikelelo Mutiti and Zoe Whitley, who each took different approaches, taught me how to be the type of facilitator who meets people halfway and allows them to find their own way of interacting with texts and engaging with the public.

Participants of Àsìkò Art School with Bisi Silva, 2014. Courtesy of Erin Rice.

What I loved most was the access Bisi gave to people you don’t normally get to meet. It was great to meet artists in a local context, as well as artists like Leo Asemota, which was incredible. This impacted me very deeply.

SB:Dana, you run Njelele Art Station, an urban art laboratory in Harare. What are your thoughts on artistic education in Zimbabwe?

DW: This is an exciting time for the Zimbabwean art scene with the global spotlight on many of our incredible artists, many of whom were trained or educated locally. It was recently announced that art will form a critical component of the new national school curriculum. Currently, there are quite a few tertiary institutions involved in arts education. In addition, there are numerous small independent spaces that generate alternative forms of knowledge production, such as Njelele Art Station. Furthermore, there is the Zimbabwe Association of Art Critics (ZAAC), which has made a significant contribution. We must not forget, however, that in art, there is a predisposition amongst artists to educate themselves, to further develop their own creative skills, to unlearn much of what they have picked up in educational institutions, and to bend and break every rule in the creative’s handbook.

SB:How can artistic residencies like Àsìkò help African artists advance in the art world?

VU: Nigeria and perhaps other African countries still need to reevaluate antiquated traditional modes of teaching art, which emphasize skill development with limited pedagogy on implementing a conceptual framework. Programs like Àsìkò create alternative platforms that attempt to fill in these gaps, consequently helping young artists in Africa find their niches while developing their intellectual depths.

Stephanie Baptist is a cultural producer, curator and editor of contemporary art from africa, diaspora and global perspectives, based in New York.

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas