Amelia Umuhire: Unpacking Hidden Rwandese Stories

12 December 2019

Magazine C&

7 min read

Contemporary And: What challenges do you face working in the two different contexts in which you live? Amelia Umuhire: It’s a very fortunate thing to be able to work in my hometown, Kigali, and chosen town, Berlin, and to call both places home. In Kigali, there’s a lot going on in the arts, be it …

Contemporary And: What challenges do you face working in the two different contexts in which you live?

Amelia Umuhire: It’s a very fortunate thing to be able to work in my hometown, Kigali, and chosen town, Berlin, and to call both places home. In Kigali, there’s a lot going on in the arts, be it film, design, fashion, art, or music. It’s growing very fast. Working with friends and colleagues with whom I share a language and also a lot of cultural references, thinking about similar things in different ways, is really pleasant.

It also rips down the sentimental nostalgic view one can develop when not working in one’s home country and allows a focus undistracted by the narrow understanding of oneself in an art context still dominated by a guilty white gaze. Often in Europe the focus is on the fact that one is African, an immigrant, a woman of color – the list goes on…. While these categories may be necessary for some in order to contextualize the work, I prefer an environment where I can be a whole self and let the work speak for itself.

The challenge in Rwanda, as in Germany, is to create work structures that can outlive the hype and to make meaningful work that can live and be seen outside of the art bubble.

C&: How would you define your position as an artist and individual within a global Diaspora?

AU: I’m too young and still at the beginning of my artistic career to position myself firmly. In terms of identity, I’m a Rwandese woman with a German passport doing film. But lately I’ve been interested in the colonial education system in Rwanda, because of the long-lasting influence it had on my parents and the generations before and after them who went through it. It’s important to know what came before, how people managed their reality and questions of identity in different circumstances. It helps detangle the present.

I went to school in Germany and became a German citizen when I was around eleven or twelve years old, and growing up I looked for answers regarding identity and the purpose that comes with it in African-American culture rather than my own.

There’s a tendency as Africans in Europe, but also elsewhere, to align ourselves too easily with African American culture and ignore the fact that we have a diverse history that is still with us and accessible through elders, institutions, and African literature.

So right now, that’s where I am, trying to identify and connect the dots. And understanding the system in which my parents grew up and in what way it shaped their values is a beginning. What was it like going to school in a space like that, where you were taught Latin and Greek by Belgian priests, and then go home in the holidays? Because the more crucial part of education happened there, at home, when the new knowledge was put into a broader context.

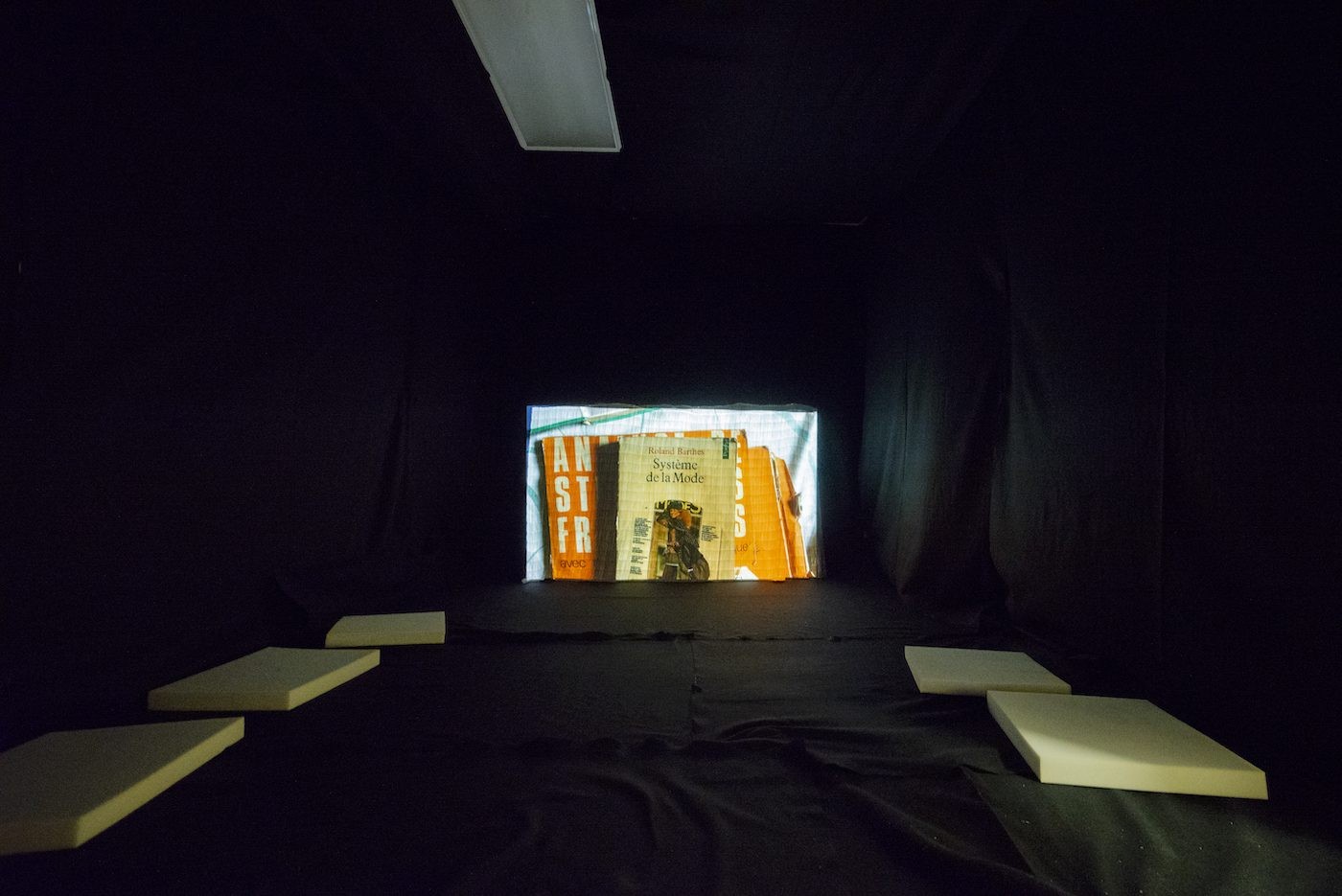

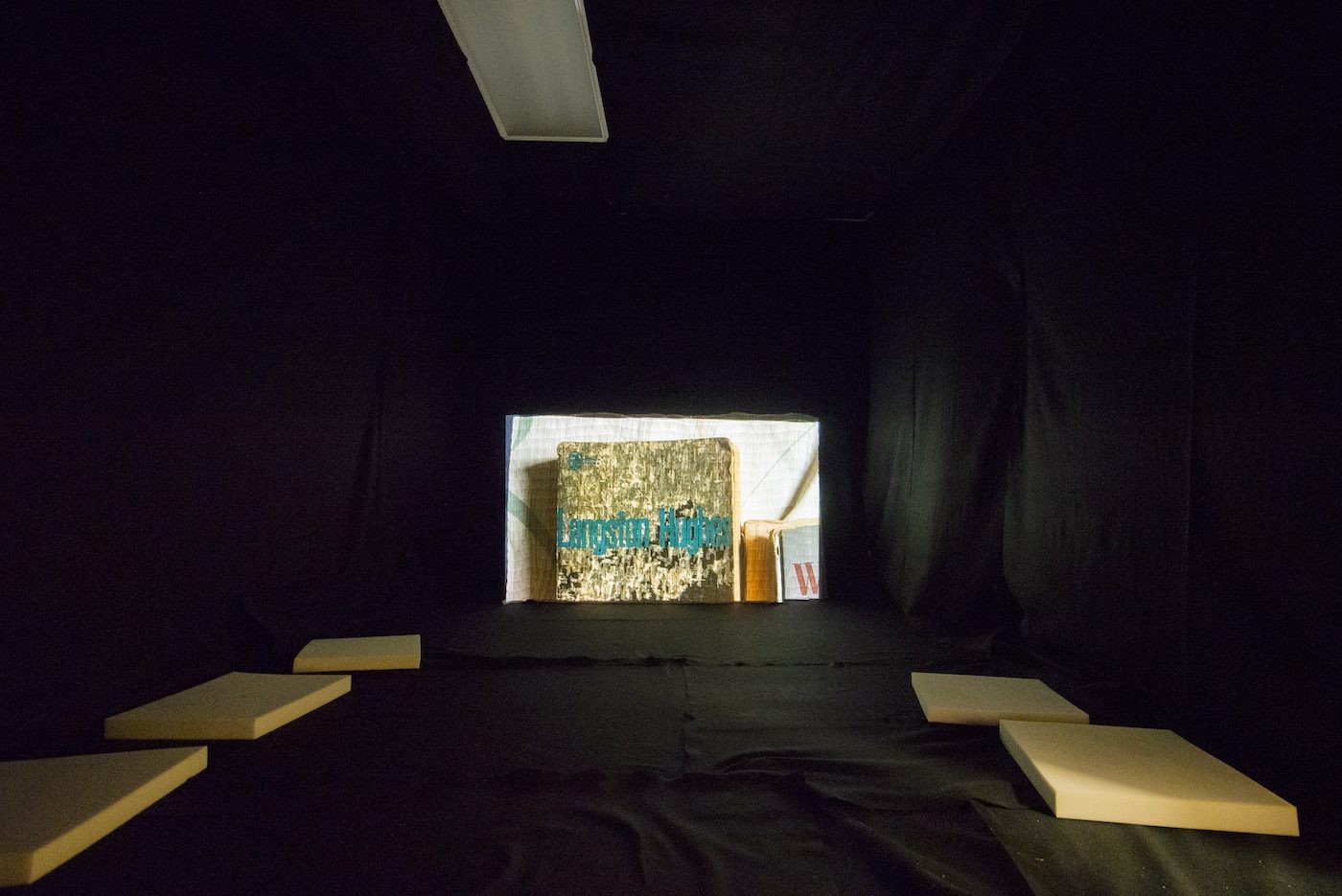

Amelia Umuhire, King Who, 2019. Video. Photo: Ronald L. Jones

C&: What draws you to the concept of Show Me Your Shelves?

AU: What I like is that the works are shown in spaces such as the African American Library at the Gregory School, the first school for freed slaves in Houston, an institution that shows the crucial part education plays in the process of emancipation.

I have been working around memory a lot, and especially tracing my father’s life through the things he left, most of those being books. So the concept aligned with the research I was already doing. I liked going back to it and thinking about his books, which my aunt has kept and preserved for over twenty-two years now. I took the title quite literally and looked at his shelves and the library of the Catholic boarding school he went to. It’s like someone left all their recent tabs open and you can trace a person’s or institution’s history, and how the two are intertwined.

And it was fun to think of how to use the space. People come to libraries to study, to focus, or for good internet, but they have to be silent and focused for a long time and are happy to be distracted by art.

C&: Could you share with us your ideas for your work in the Show Me Your Shelves exhibition?

AU: King Who is a video installation in which a five-minute video is projected in a loop on ikirago, a woven Rwandese mat we used to sit on as kids at big gatherings or anywhere else where chairs were rare or reserved for elders. The video begins in Kigali, at my aunt’s place on a rainy afternoon. She is over eighty years old and we have our little routine of small talk and jokes. She has been quietly keeping my father’s books in a small room in the back of the compound.

Then we’re in the books, following the reoccurring stamp of College Christ Roi to its origin. It’s a college founded in 1956 in Nyanza, the former capital of the former Kingdom of Rwanda, and it is still considered one of the best schools in the country.

Next to the college there’s the church in which King Mutara III Rudahigwa put the country under “King Christ’s” protection [in 1943] after converting to Roman Catholicism and taking on the names Charles Léon Pierre. His father had been exiled by the Belgians for having refused to convert and now his son, in a fatal symbolic act, traded his people’s beliefs for what he thought of as political modernization efforts. The same king initiated the founding of schools like College Christ Roi. He’s an interesting and tragic figure who was later killed by the Belgian colonialists.

Thinking about the generational conflict, the lethal pressure of the colonial regime and everything that might have led to his actions, I found a video of one of his visits to Belgium, most likely from 1949, where he sits down in the back of a convertible and loses his crown. The queen, his wife, politely gives it back to him, and after putting it back on he glances over to the camera, like you do when you fall down and hope no one saw you. There’s another video where the king is dressed in a dapper western suit with a western hat, getting out of a plane and losing his hat again.

Both videos are narrated by a jolly Belgian man in a patronizing voiceover, recalling his colleagues’ failed attempts to dance with the king’s wife and other demeaning anecdotes from their stay in the land of Tintin and Leopold II.

So the piece is a visual representation of all these thoughts and questions condensed into a five-minute video, with a slightly haunting electronic score I composed.

Amelia Umuhire is a Kigali- and Berlin-based filmmaker known for her cinematic three-part YouTube series Polyglot (2015), the experimental short film Mugabo (2017) and the Prix Europa-nominated radio piece Vaterland (2018). She is the recipient of the Villa Romana Prize 2020.

Mearg Negusse studied Art History and Philosophy. She is based in Frankfurt am Main.

This text was commissioned within the framework of the project “Show me your Shelves”, which is funded by and is part of the yearlong campaign “Wunderbar Together (“Deutschlandjahr USA”/The Year of German-American Friendship) by the German Foreign Office.

from

Feature

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

A Collector’s Guide to São Paulo

from

Film screening

On History and Fiction: Tuan Andrew Nguyen's Cinematic Memory Work

Lebohang Kganye Awarded Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2024