Alive, Awake, and Conscious

. From his office window, curator Jay Pather sees his country of South Africa metaphorically as a burning residential shack. When there is an occasional fire in a township, the authorities and the public respond by investigating the cause of the accident – was it an arson, or negligence, like an unattended candle? But people …

.

From his office window, curator Jay Pather sees his country of South Africa metaphorically as a burning residential shack. When there is an occasional fire in a township, the authorities and the public respond by investigating the cause of the accident – was it an arson, or negligence, like an unattended candle? But people rarely ask why there is a shack in the first place, why there are such underserved conditions unfit for human habitation.

“We seem to always wait for a crisis to deal with age-old problems” says Pather about post-apartheid South Africa, a society that deals with symptoms and not structural problems. “We view them superficially, as if they are happening for the first time.”

We had met to discuss art, not politics. During the brief conversation, it became clear that the two go hand in hand. At least when it comes to the upcomingLive Art Festival, which he founded and curates. “Live art is a way of grappling with the deeply embedded contradictions of the promised free nation and the inherited darkness” he says. “Artists are finding live, interdisciplinary art as a medium that embraces the complexities of living in a post-colonial society.”

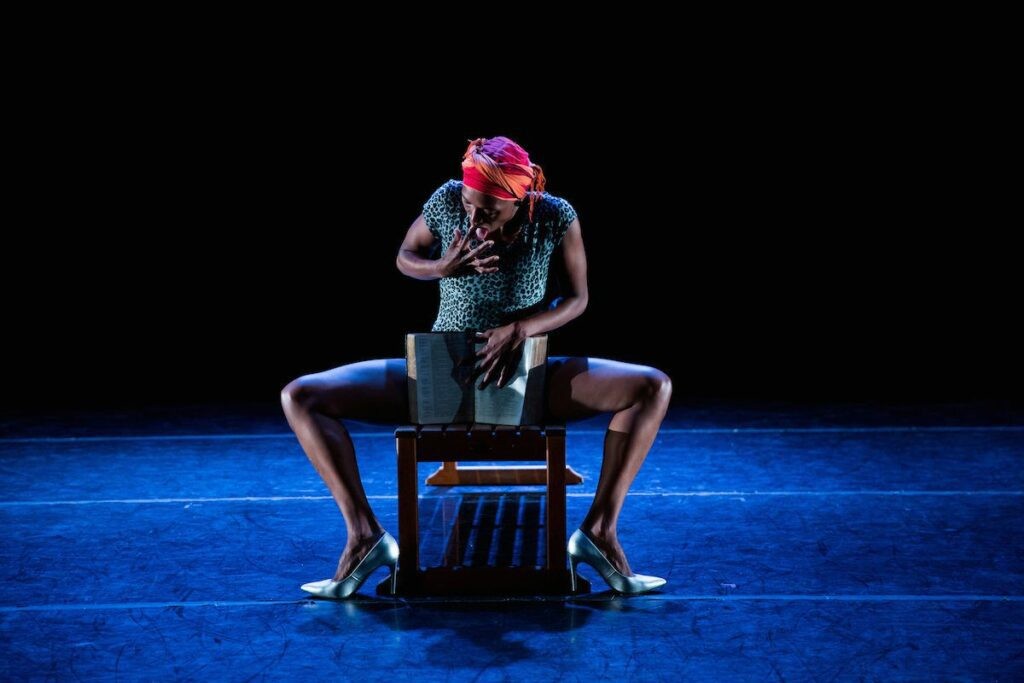

Mamela Nyamza in DE-APART-HATE. Photo by Jonathan Hsu.

With the theme of grappling with the post-colonial moment in mind, Pather gathered 34 artists from 12 countries to perform at the3rd Cape Town International Live Art Festival on 10 —26 February. Amongst the local artists are established award winners such as Mamela Nyamza, Donna Kukama, Steven Cohen, and Zanele Muholi, together with UCT post-grad performance students. The international line-up includes performers from Nigeria, Mozambique, India, Japan, and England.

“Some will make you think about history, class, gender, and race. Artists are encouraged to stay true to what they want to do. Colonialism was about one homogeneous set of values – ‘only one right way’ was the logic we had to buy into. I’m interested in destabilizing and deconstructing this logic. Criticality is all we have in order to go to the next stage.”

And what one can expect in this next stage? Back to the greater politics, Pather says that “the pots are boiling and we are now experiencing a spilling over and you can’t put the lid back on. Artists address this spilling over of emotions that have been kept in during apartheid.”

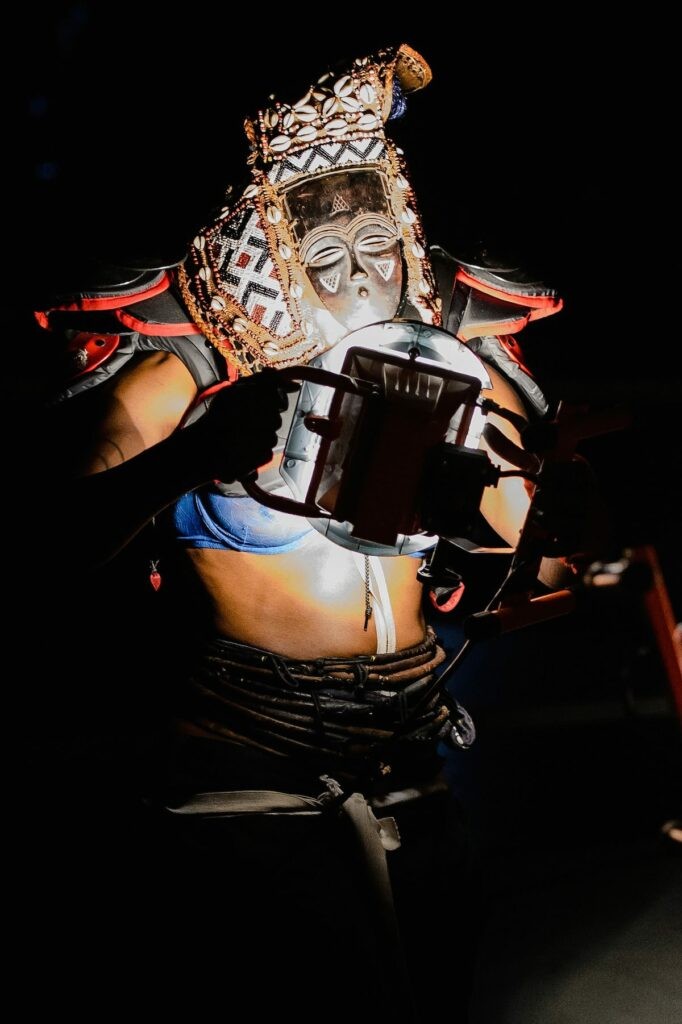

Buhlebezwe Siwani & Chuma Sopotela in ‘Those Ghels’ – Photo courtesy of the artists

The country’s politics are what inspired him to get involved in the arts in the first place. “I developed a political consciousness growing up under apartheid simply because I was looking for ideas to help me understand a divided and violent society. I found that reducing the complexities and making the human simple is the root of violence. De-humanization is a big issue in the economic state of the country. We have to regain the human by finding complexity, so one wouldn’t be lazy about approaching the human being.”

“Live artists explore how it is to be alive and sensitive to the complexity of the person next to you. We have reductive ways of talking. I came to live art when looking for forms to express complexity, how we structure thought and deconstruct this. Live art forces you to confront complexity with a fresh energy; it is a flag for being alive, awake, and conscious.”

Cape Town is celebrated as the creative hub of Africa, with mainstream festivals like the Art Fair and International Jazz Festival, but also a broke city, metaphorically, socially, and financially. The city lives with huge inequality, which makes it outstanding that Live Art Festival is free to attend. Together with the sophisticated and political nature of the content, the festival is an anomaly. Maybe an anomaly is what this city needs.

Nora Chipaumire – Photo by Gennadi Novash

“Cape Town has an open mind to non-commercial happenings. Historically, experiments do seem to happen in Cape Town, for all its divided topography. Live art is non-commercial – you can’t put it on auction or hang it on the wall. You can only feel it in the moment. We make it free partly so the audience can take risks themselves and extend their sense of what they may be comfortable with or inspired by. We want to push the limits on what we think audiences would like to experience. We expose audiences to sophisticated and award-winning, yet non-commercial work.”

He recalls how in the early days of democracy there was a lot of live art happening around, but enthusiasm faded as the economy made it difficult to sustain. “There is no steady climate. That’s why this platform is important.” One of the main challenges of the festival is “audience development,” a euphemism for the difficulty of attracting a black audience from the townships. “The arts and culture underbelly of Cape Town still does comprise a tight elite gallery circuit. We have taken reaching beyond that seriously.” He says that he has seen some improvement over the five years since he launched the festival, as the director of UCT-based Institute for Creative Arts (ICA). “In the last festival, we saw new audiences as well as young faces, and I hope this trend grows.”

Feature

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Feature

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025