Senga Nengudi

Senga Nengudi

4 June 2019

Closes: 13 July 2019

The work of Senga Nengudi has been at the forefront of sculptural, performative, and photographic practices for over forty years. Using simple materials in innovative, unexpected ways, Nengudi’s compositions evoke a rich array of references, from subtle allusions to the body, to feminist considerations of space and movement, to the confluence of different cultural and religious rituals. With equal parts rigor and grace, they encourage us to rethink our relationship to the people and world around us. Monika Sprüth and Philomene Magers are honored to present an overview of Nengudi’s work at Sprüth Magers, London, which has evolved from the artist’s recent exhibition at Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, and highlights the scope of her wide-ranging, influential oeuvre.

After studying art and dance in California and Japan, and receiving her master’s degree in sculpture from California State University, Los Angeles, Nengudi became a key participant in the young African American avant-garde in both Los Angeles and New York in the 1970s and 1980s, alongside artists such as David Hammons and Maren Hassinger. She developed early on her renowned sculptural series, R.S.V.P. (begun in 1975), which incorporates nylon stockings as well as every-day and industrial materials into supple, entwining sculptures that recall attenuated bodies, viscera and other organic matter. Though these have come to represent her work, at the same time they offer only one window into her diverse, multidisciplinary approach that likewise encompasses large-scale installations, performance photographs and videos, and objects combining plastics, liquid, pigments, and sand.

At Sprüth Magers, London, the centerpiece of the exhibition is Nengudi’s monumental installation Bulemia (1990/2018), recently recreated at the Henry Moore Institute for the first time since its original presentation in 1990. Inside a specially constructed room, the walls are covered in an abundant collage of recent newspapers: some affixed flat, others pinned at one corner, hanging loosely from the wall, while others still are crumpled into tight nuggets sprayed with gold paint. The articles Nengudi has incorporated relate to civil rights issues affecting the African American community, but rather than excising them from the page, the artist includes the entire sheet so that all of the newspaper’s additional context remains intact, including advertisements, weather reports, and other articles. Nengudi’s layered installation suggests a geological structure, in which the articles have gathered into numerous lines of sediment awaiting exhumation and discovery. Bulemia also stands as an allegory of the creative process, particularly its call for self-reflection, digestion of knowledge, and productive reemergence.

The exhibition also highlights the breadth and ingenuity of Nengudi’s practice of performance photography, through the inclusion of several singular and serial photographs. In Performance Piece (1978), for example, a dancer engages with one of the artist’s nylon R.S.V.P. sculptures, arching and contorting her body in relation to the works’ knotted, pliable strands. Flying (1982/2014), a suite of eight photographs printed and presented here for the very first time, captures members of the artist collective Studio Z (including Nengudi and fellow artist-performer Maren Hassinger) as they make sound and perform improvisationally before a white stone edifice. Often moving in unison, their bodies create dramatic shapes, taking on the look of an ancient architectural frieze as if it had peeled away from the building façade and come to life. In other photographs, the artist herself poses with more of her sculptures, partially concealed and assuming otherworldly auras.

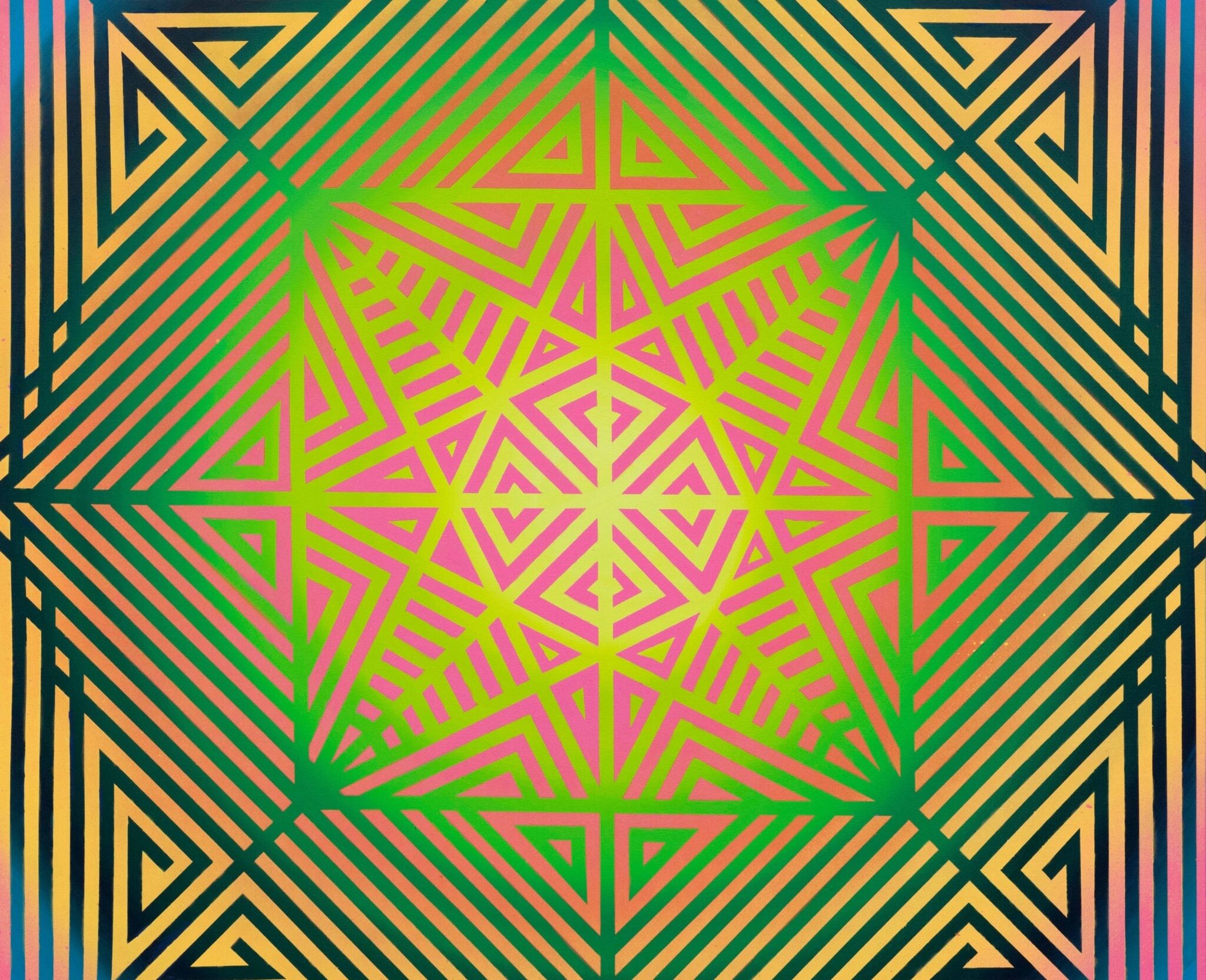

Over the years, Nengudi has experimented with unconventional substances to produce arrangements of paintings and sculptures influenced by various concepts of ritual. In Sandmining (2018), a field of sand covers the floor, some areas of which are molded into pyramid-like, ceremonial mounds. Powdered pigments add dashes of color, while twisting metal exhaust pipes emerge from the sand like plant tendrils or appendages. Inspired by Native American healing rituals, but also reminiscent of Zen gardens and even gestural painting, the installation is joined by examples of Nengudi’s Wet Night – Early Dawn – Scat Chant – Pilgrim’s Song (1996/2017), a series of wallworks that comprise spray-painted cardboard panels encased in aqua-colored plastic sheets. Though such materials may be industrially made, the symbolism of the painted compositions and the content of the works’ titles draw connections to music, poetry, and the natural world.

These works and a selection of recent sculptures, which return to themes and materials found in her earliest sculptures, make clear the importance of Nengudi’s work to the development and legacy of postminimalism. As in the work of artists such as Eva Hesse, Bruce Nauman, and Judy Chicago (the latter two who, like Nengudi, were also practicing art in Southern California beginning in the late 1960s), her Water Compositions (1969–70/2018) play with color, malleability, and embodiment. Inside transparent, heat-sealed vinyl casings, candy-hued water gives shape and visual punch to drooping plastic forms.

In Nengudi’s newest series, A.C.Q. (short for Air Conditioning Queen), recently on view in the 57th Venice Biennale (2017), the artist reprises her work with stockings in sculptures that explore further the inherent strength and ephemerality of the nylon medium. A.C.Q. III (2016–17) echoes the shape of a body, splayed out in a manner that could be read as majestically flying, or possibly violently suspended. In A.C.Q. I (2016–17), the artist has combined tied, knotted and sand-filled stretches of pantyhose with refrigerator and air conditioner parts, creating a kind of stage set within which the hose flutter gently, guided by the machines’ fans. Always pushing her work forward, while folding in important, longstanding inquiries, Nengudi continues to create highly original and evocative works that feel as groundbreaking today as they did in decades past.

Senga Nengudi (born 1943, Chicago) lives and works in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Solo exhibitions include those at Lenbachhaus, Munich (forthcoming, fall 2019), Henry Moore Foundation (2018), USC Fisher Museum of Art, Los Angeles (2018), Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami (2017), Contemporary Arts Center New Orleans (2017), Henry Art Gallery, Seattle (2016), and Museum of Contemporary Art, Denver (2014). Her work has been included in numerous groups exhibitions, many of which have traveled extensively, including most recently the 57th Venice Biennale (2017), Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, Tate Modern (2017); We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85, Brooklyn Museum, New York (2017); Blues for Smoke, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2013); Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art, Contemporary Art Museum Houston (2012); Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles, 1960–1980, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2011); and WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles (2007).

View more from

Beyond Representation

Tierras reimaginadas: migración

Jangueando: Recent Acquisitions

Nigerian Modernism – Group Show

Oct 8, 2025–May 10, 2026

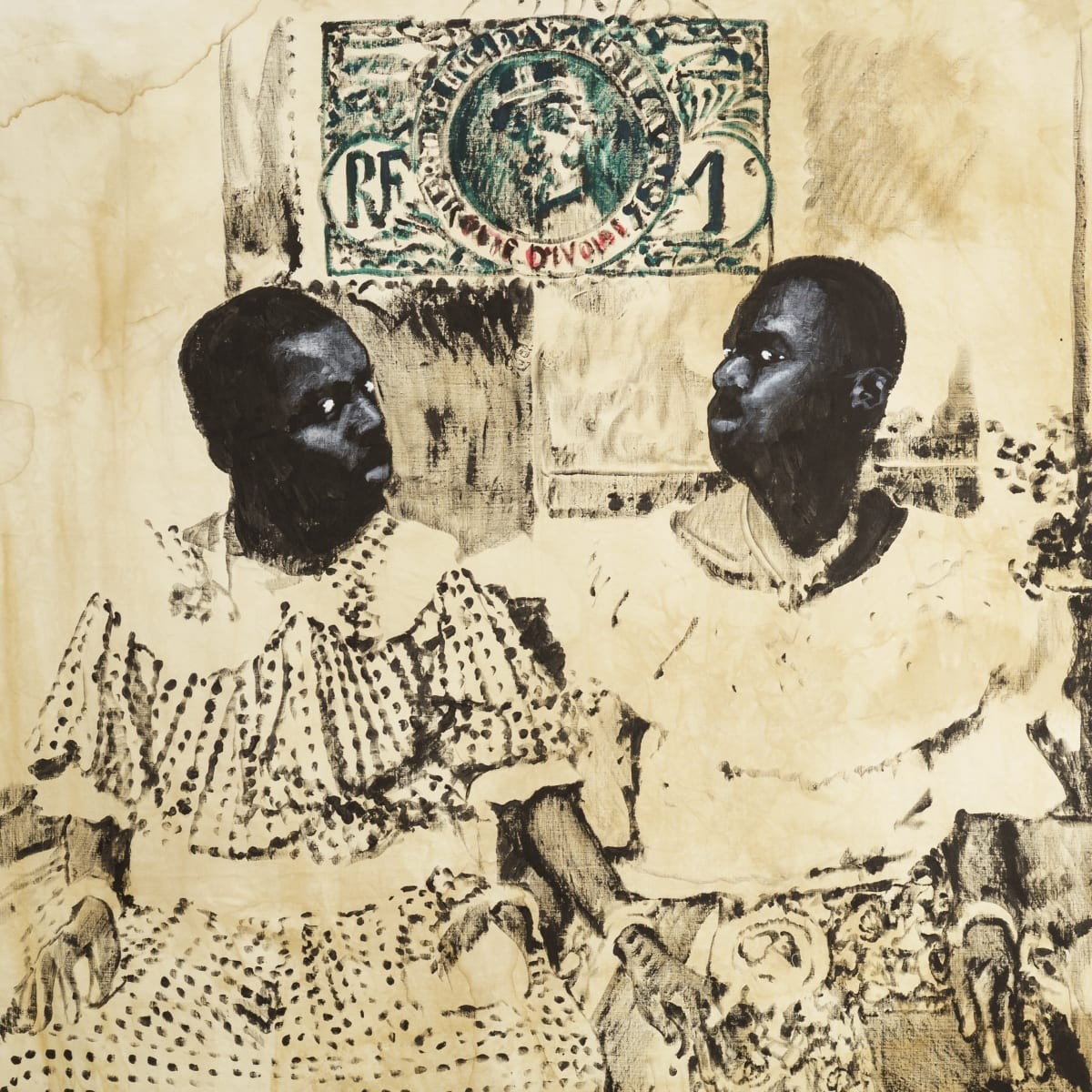

Roméo Mivekannin: Correspondances

Oct 2, 2025–Mar 21, 2026

The Writing’s on the Wall (TWTW)

Sep 13, 2025–Mar 14, 2026