Tracing the Then and Now of Restitution Through Mati Diop’s Documentary Fantasy Dahomey

Can the French restitution of some of Benin’s royal treasures constitute a new beginning? Olivia Gilmore explores this question alongside Mati Diop’s new film, Dahomey.

Was the historic restitution of twenty-six artworks and sacred objects to Benin by France in 2021 – as chronicled by Mati Diop’s “documentary fantasy” Dahomey (2024) – merely a band-aid on the deep wounds of colonialism? While celebration is due, and Diop captures the repatriation poetically in her mesmerizing film, we cannot forget the years of efforts ignored by colonial France since Benin’s independence in 1960. Thanks to the Golden Bear-winning Dahomey, this conversation has been restarted three years after the royal objects’ return, prompting us to ask what the next steps should be.

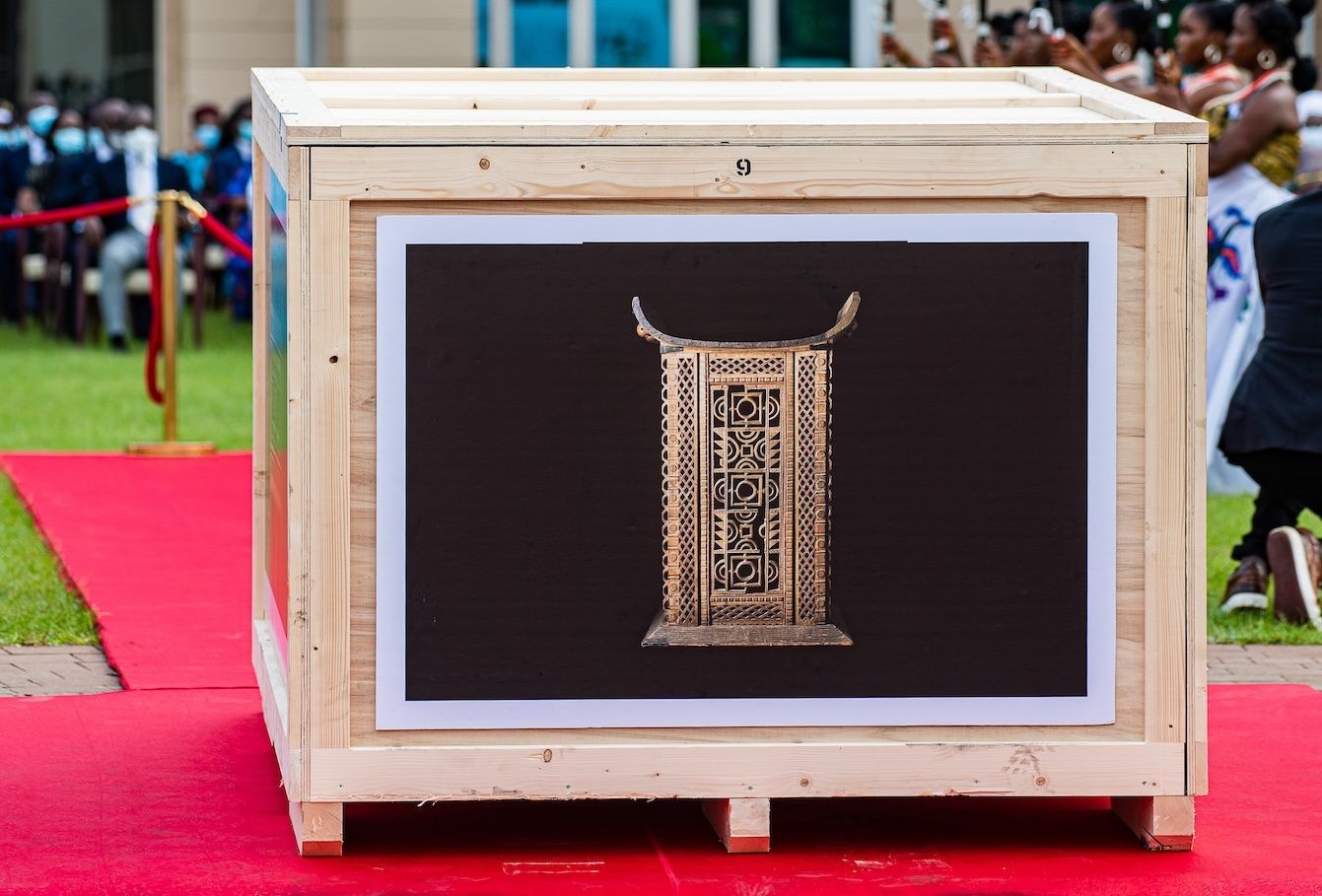

One of 26 works from the Royal Treasures of Benin at Official Welcoming Ceremony at the Marina Palace.

Diop’s film begins at the Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, on the day of deinstallation of those artworks to be transported back to the Kingdom of Dahomey, now modern-day Benin, a land that has not seen them in 130 years. We watch as a team of art handlers painstakingly remove the pieces from their metal brackets, plinths, and pedestals while curators Calixte Biah and Alain Godonou look on. The twenty-six treasures, not all shown, include three royal statues (bochios) named after kings of Dahomey, asẽn altars, a stool, thrones, a carved calabash lid, carved doors, scepters, a spindle, a loom, clothing, and a leather bag. In the museum, time moves ever so slowly. If we become impatient watching the minutia, imagine how the people of Benin or the objects themselves have felt – waiting all these years, never believing that the day would ever come. Some equated the possibility of any repatriation to the fall of the Berlin Wall, an impossibility until it happened.

C’est de la poudre aux yeux, wrote the lawyer Roland Adjovi in a 2021 article, just a month before the return of the royal objects: flattering at its face but in reality a deception – the French equivalent of smoke and mirrors. The first major flaw of the process, he pointed out, was that France wanted to dictate the terms of the restitution – a ludicrous result of years of colonialization: the normalization of terms that favor the plunderers. Anything taken by unfair means should be returned to those it was taken from, no questions asked. To paraphrase, Adjovi argued that the only adequate restitution would be the return to the status quo ante, a restitution in integrum: the return of all objects taken during the colonial period, between 1400 to 1960, through unfair sales contracts, seizures by foreign authorities, or theft (sometimes in the form of military expeditions).

Still from Dahomey by Matt Diop.

Back onscreen after deinstallation, the treasures are placed into boxes and shackled. We follow, plunged into an unknowable darkness: a pitch black is before us while the ethereal voice of King Ghézo – half-man, half-bird – speaks in Fon. The French subtitles of this monologue, written and spoken by Haitian writer Makenzy Orcel, are gender fluid: “I am no longer number twenty-six.” It is appropriate, Diop’s decision to give these treasures voices, as Indigenous practices before colonial influence were widely animistic. King Ghézo ponders what awaits on the other side of the journey: will he recognize home? In contrast to the original trip made across the Atlantic in the bowels of a ship, the objects fly home above the ocean.

In 1892 French Colonel Alfred Amédée Dodds invaded Dahomey’s capital, Abomey, and looted the royal palace under the rule of King Behanzin. After that theft, the objects were “given” to the Musée d’ethnographie du Trocadero and later “acquired” by the Musée du quai Branly. As early as 1960, with the liberation of Benin from French rule, people have pushed for the repatriation of the thousands of objects taken from Africa during France’s colonial plunders. These efforts gained momentum in the late 1970s, when UNESCO Director Amadou-Mahtar M’Bow called for rebalancing the world’s heritage between North and South in “A Plea for the restitution of an irreplaceable cultural heritage to those who created it.” This formal request was disregarded. Calls persisted from multiple quarters, and in 1982, Louvre Director Pierre Quoniam issued a report favoring the restitution of African heritage. Also disregarded. Finally, in 2016, at the request of Beninese President Patrice Talon, his Minister of Foreign Affairs Aurélien Agbénonci asked that France return the zoomorphic and royal insignia of Benin, emphasizing their value as both historical and spiritual. In 2017 French President Emmanuel Macron gave a speech in favor of restitution, before commissioning the seminal 2018 report by Bénédicte Savoy and Felwine Sarr.

Diop shows the plane land in Benin and then trucks driving through the streets to the Palais de la Marina, the designated exhibition space. Dancers, music, and crowds greet the trucks as they pass. On opening night the mood is celebratory and reverent as Benin residents see the twenty-six objects for the first time.

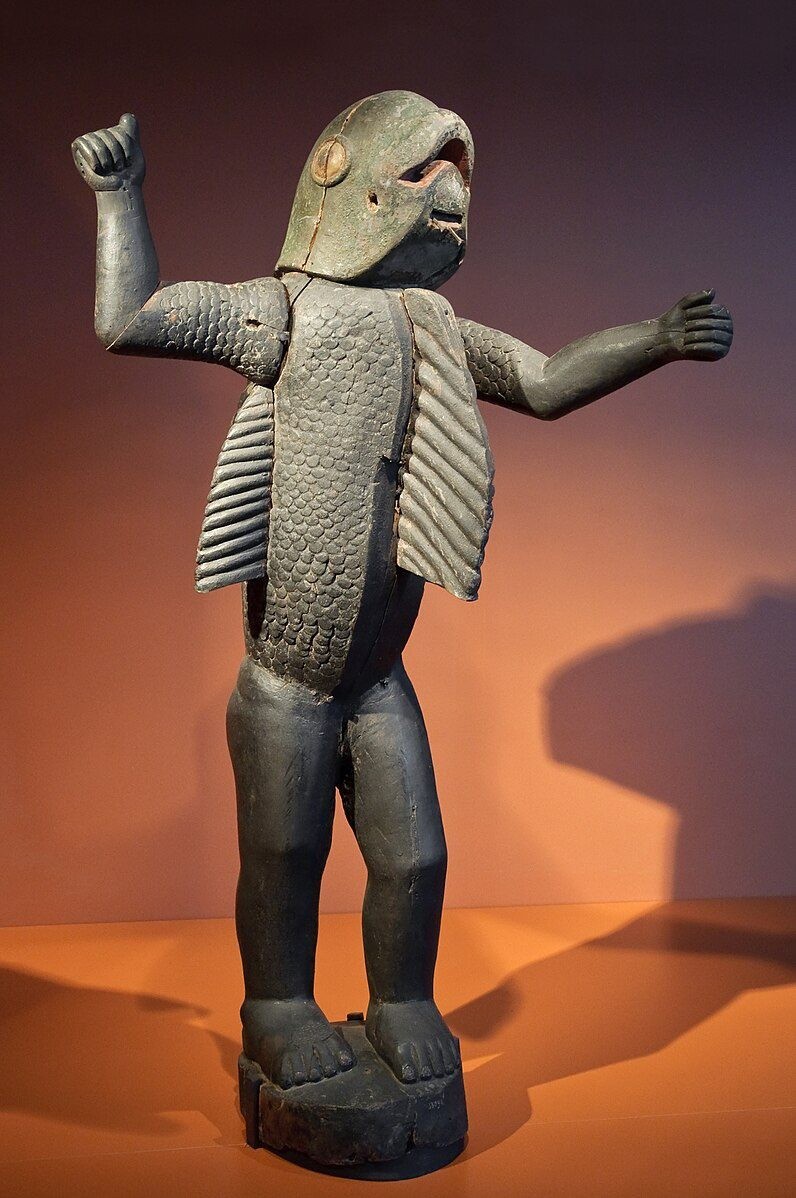

“Shark-Man” (circa 1890) – Kingdom of Dahomey. This statue would represent Béhanzin, the last king of Dahomey. His coat of arms featured a shark. To announce his intention to fight the French fleet which was stationing at Cotonou and crossed the sandbar every day, Béhanzin compared himself to the shark: “the daring shark has troubled the sandbar” (“gbo ouele fandan agbedui brou”).

According to Sarr and Savoy in “Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain. Vers une nouvelle ethique relationnelle” (in English, “The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage”), in 2018 some 90,000 African works remained in French museums – nearly half having arrived in the colonial era. The silence around this fact had been preserved by European museums, newspapers, and ministries of foreign affairs, Sarr and Savoy pointed out. A more recent example of this same silence can be seen in the Musée du quai Branley’s press kit for the 2021 exhibition of the twenty-six royal treasures from Abomey before repatriation: it contains a timeline which abruptly jumps from 1960 to 2016 – the erasure of fifty-six years – as if no one had ever tried to retrieve the thousands of pillaged objects from France before the official request made by the government of Benin.

In the film, a debate takes place in an agora-like space between students and researchers of the University of Abomey-Calavi. We witness Dahomey assistant director Gildas Adannou ask in French, “Did you know thousands of Beninese artifacts were held overseas? If yes, at what point in your life did you find out?” Someone responds: “I grew up on Disney. I grew up watching Avatar. I grew up watching Tom & Jerry, but I didn’t grow up watching an animated movie that was focused on Béhanzin, that focused on our cultural heritage. During my childhood, therefore, I was never made aware that artifacts belonging to us had been deported and would return who knows when.” We might have the same experience – of the Global North’s media hegemony promulgating its cultural identity throughout the world while erasing others’ rich histories and cultures through omission. Ultimately the students and the audience are left with more questions than answers.

In the final scenes of Dahomey, dusk becomes night. The camera sways through space to the otherworldly voice of King Ghézo: Je me sens attiré.e par quelque chose de très ancien comme une invitation, un possible recommencement. We are thrust into a lush tree; the spirit reacquaints themself with the surroundings of their homeland. Again we see viewers pensively attending the exhibition at the Palais; a street vendor’s colorful books arranged neatly in columns in the sunlight – French author Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Du contrat social above Senegalese author Cheikh Hamidou Kane’s L’Aventure ambiguë; the shore of the Atlantic in Cotonou as the sky becomes increasingly dark. Finally, wandering through the streets of the city, the spirit takes us with them as they glide past the phosphorescent neon lights of restaurants, clubs, bars – people enjoying the warm evening. A sense of possibility and curiosity awakens within us through this dreamscape. Perhaps it is new beginning – on a metaphysical level at least – despite the future challenges of restitution and decolonization.

Olivia Gilmore is an American writer, photographer, and curator based in Paris, France. Her work has been featured in Contemporary And, Passerby, Université d’été de la Bibliothèque Kandinsky: 7e édition, The Brooklyn Rail, Runner Magazine, Detroit Art Review, Essay’d, and TagTagTag Magazine, among others.

from

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

from

Feature

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge