POLITICS & SOCIALIST ART

28 August 2014

Magazine C&

6 min read

It was the lead up to the first anniversary rally of South Africa’s second strongest and youngest opposition party, the Economic Freedom Fighters. The party anticipated that thousands of its supporters, probably in the party’s red overall and beret uniform, would take to Thokoza Park in Soweto to celebrate the EFF’s first birthday. If it …

It was the lead up to the first anniversary rally of South Africa’s second strongest and youngest opposition party, the Economic Freedom Fighters. The party anticipated that thousands of its supporters, probably in the party’s red overall and beret uniform, would take to Thokoza Park in Soweto to celebrate the EFF’s first birthday.

If it were a painting, the gathering might abstractly bring to mind Karl Hofer’s 1947 Night of Ruins, or more literally Diego Rivera’s 1956 May Day Procession in Moscow. Or at least that’s what past EFF events have evoked. It was roughly around the same time in 2013 that the expelled leader of the ruling party’s youth league and enfant terrible, Julius Malema, launched his “Marxist-Leninist and Fanonian” party along with the party’s striking insignia and communist-themed uniform.

In a country where the liberation party, the ANC, has lost supporters as corruption charges plague its president, Jacob Zuma, through its continued dedication to neoliberal economic dogmas, this new socialist-styled party that aligns itself with the workers and their economic emancipation – despite Malema facing his own corruption cases – has become a recognizable force in South African politics. The party has even seized the radical and socialist rhetoric space once claimed by the South African Communist Party and the ANC Youth League.

.

And in its first year, as the movement grew larger – starting from a ripple of 1000 members and eventually forming a solid red wave of over one million voters in South Africa’s 2014 election – the party’s aesthetic has become more recognizable and its presence more felt.

EFF is everywhere – on posters lining the streets, spray-painted logos on walls as well as online – and its insignia is unavoidable: a black-clenched fist, wrapped around a spear, shoots from the southern tip of Africa into the greater continent – with an oil derrick and a star on either end.

.

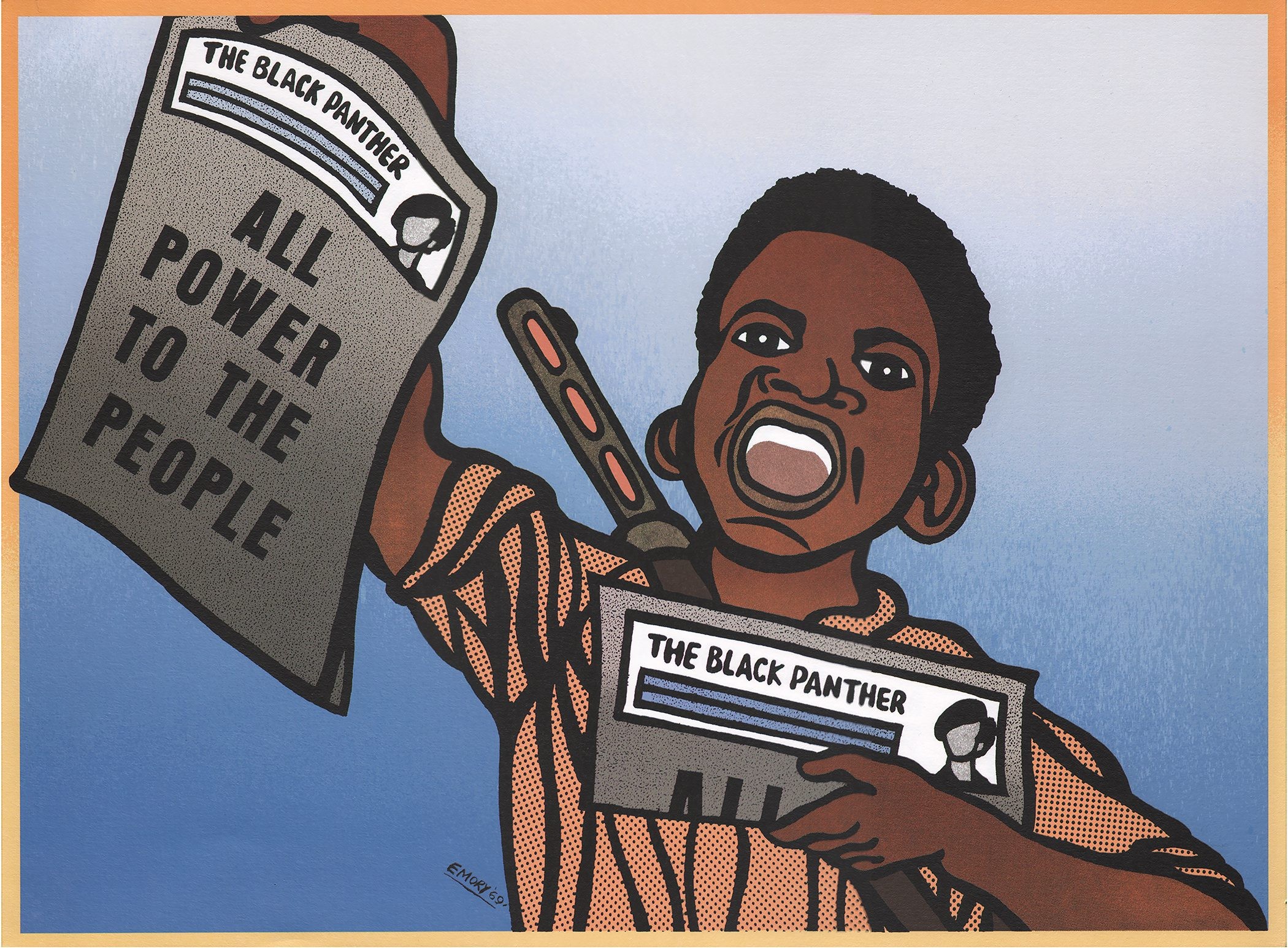

This image, its logo, is an African nationalist ode to the party’s push for land expropriation without compensation, and the nationalization of the strategic sectors of the economy. The raised fist, a common struggle image, is bold and a reminder of Spanish Civil War posters of the late 1930s, and of South Africa’s Black Consciousness Movement led by Steve Biko. While the five-pointed communist star is widely believed to signify the five fingers on the workers’ hands. And the oil derrick, seen to represent the party’s policy to nationalize the country’s mines, is a throwback to, among others, communist China, where, from 1949, drilling rigs and factories produced propaganda posters about Chinese Communist Party leader Mao Zedong establishing the industrialization of the People’s Republic of China.

.

This connection between the imagery that has emerged from Mao’s time in leadership and the EFF’s launch isn’t lost on the South African party.

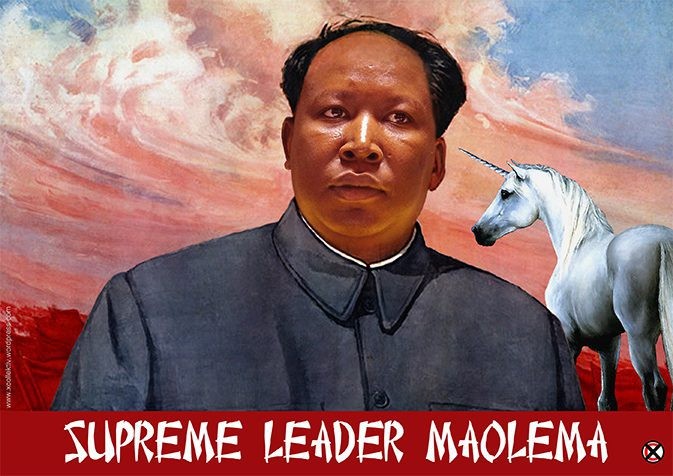

Shortly after launching its election manifesto in Tembisa, just outside of Johannesburg, in March, two months before the country’s general elections, a photograph of a crowd carrying a large portrait of a solemn-looking Malema, in a red beret and shirt, floated around on the internet. In his column for a local publication, EFF MP Andile Mngxitama remembers the event.“… A hundred meters from the stage, there emerged a portrait of Malema in the profile of China's erstwhile leader Mao Zedong. It was hoisted high above the multitudes of red. It was an ecstatic moment of symbolic reconstitution of the 60,000 into a single force in the form of Malema as Mao.”

Not only was Mngxitama accused of idolatry, his column gave birth to South African art collective Xcollektiv’s superimposed image of Malema on a famous Mao image. In plain clothes ahead of a storm cloud and a white unicorn, Malema is painted with a red-flushed face. Speaking to the LA Times, an artist who retouched the three-story high portrait of Zedong hanging over Tiananmen Square, says there’s a reason for the painted-on complexion:

“Mao's face must be painted extra red to show his robust spirit. It can never be too yellow, which would seem sickly, like he hadn't eaten in days. You could be accused of being a counterrevolutionary.” And from 1960, Zedong’s People’s Liberation Army was increasingly “employed to bolster the personality cult around Mao, and thus to produce art that would contribute to the construction of Mao's god-like image,” according tochineseposters.net.

.

But the cult of personality or idolization of one leader, in the style of the Malema poster, Mao Zedong at Tiananmen Square, or even pervasive images and effigies of Joseph Stalin while heading the Soviet Union, was denounced even by the founders of Marxist theory, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, according to a 1956 speech by Nikita Khrushchev, first secretary of the Communist Party after Stalin’s death three years earlier. “Both Marx and I have always been against any public manifestation with regard to individuals, with the exception of cases when it had an important purpose. We most strongly opposed such manifestations which during our lifetime concerned us personally,” said Engels.

.

Extending on Engels’s thoughts, Xcollektiv, who are known to critique politicians through satire, point out that revolutionary theorist Frantz Fanon “with whom EFF claims philosophical identification … was also critical of this hero-leader worship.”

.

Going back to the “Mao’lema” poster of Malema as Mao at the rally, Xcollektiv – whose members choose to remain anonymous – tells me that the “caricature was meant to say, sure, in a sense, Malema is a lot like Mao because they were strong leaders.” But this representation of Malema as a god-like figure is problematic according to the collective, because “uncritical support of leadership inevitably leads to the betrayal of the revolution.”

.

And as Malema – clad in a beret in the style of EFF muse Thomas Sankara – appears in the media ahead of his party’s first anniversary rally, it’s hard to avoid the personality cult issues that surround his representation. Along with this, we can envisage other potential artistic manifestations the party might provide as it continues to add a fiery tinge to the country’s political horizon, which once seemed pretentiously rainbow-colored after the fall of apartheid.

Stefanie Jason lives in Johannesburg and is a content producer and arts writer for South African publication Mail & Guardian. Her writing focus is on visual arts in the country and music.

from

Feature

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

A Collector’s Guide to São Paulo

from

Political art

Art in Support of Political Change

Hungarofuturism and its Parallels with Afrofuturism