On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

Pan African Solidarity School logo, designed by Sheyi Adebayo

This hybrid conversation between artist-curators Ethel Tawe and Neema Githere engages with the expansiveness of the digital diaspora and what it means to practise across time zones. Githere sheds light on exile and relational repair on and offline.

This conversation was held between May and June 2025, both online and in-person. Its hybrid space-time format is pertinent to the ways in which Neema Githere and I have related over the years as co-conspirators in curating and reimagining digital protocols. Neema is a Kenyan-born writer, artist, relational architect and guerrilla theorist, whose practice examines the digital diaspora and networked repair through cyber-cartography, with a focus on Afropresentism, an inquiry into how descendants of exile can invoke somatic attunement amidst systematised algorithmic displacement. Using Data Healing, an experimental practice that explores the links between technology, nature and spirituality, Neema does not limit herself to the analysis of conditions, but proposes new strategies to combat the data trauma that saturates our virtual worlds. Neema was recently appointed co-curator of Transmediale 2026, an annual festival on cultural transformation within media and technology, and a transversal platform which in this edition will not be understood as a static event but as a living carrier net—an assemblage of practices, temporalities and geographies that challenge conventional narratives of progress and innovation. The first bulk of this conversation was recorded online with an AI-generated transcript, while the second is generated from memory after being held AFK (away from keyboard) at a C& retreat in Europe.

URL (Online Call)

May 27, 2025

Geolocation [Ethel]: 51.5074° N, 0.1278° W

Geolocation [Neema]: 1.2921° S, 36.8219° E

It’s been a restless month. I just returned from a research trip to Benin City Nigeria, and I’m planning a long-awaited visit to my birthplace in Yaoundé, Cameroon, after over 13 years. I had been casting bronze in Benin using traditional methods, a tedious process which heightened my regard for this ancient city’s guild and its cultural significance in the artworld. In Benin, I was only about a thousand kilometres away from Yaoundé, and the equatorial sun and red soil made that proximity vivid. However, transit lines, borders and identity politics—the underbelly of Black geographies of exile—had kept me away from home for over a decade, until soon.

As I wait for Neema to join our meeting link, I’m thinking about why my upcoming route from London to Yaoundé—a former French colony—has a layover in Paris. I’m thinking about colonial remnants in our movements, and the crippling physiological, psychological and environmental cost, such as increased air mileage and gas emissions. I am thinking about how many gallons of water it takes to power this meeting, as per a recent TikTok. Neema picks up.

We happen to both be calling in from our beds; she in Nairobi and I in London. There is a time difference of two hours and our circadian rhythms—the body’s internal clock—have been disrupted by the events of recent weeks. Neema has recently been attending convenings and research trips as part of her continual fieldwork spanning from the Amazon River to Ouagadougou, Venice, and beyond. Last summer, she was charting her way through Melanesia, encountering traditional sea navigators and their teachings on indigenous wayfinding, as well as documenting the sacred geometry of Vanuatu sand drawings. While the critical findings emerging from such work are immeasurable, they require sustainable methods of refuelling and rest. What does it mean to survive and thrive as an artist / curator / cultural worker of African descent in this extractive global landscape? What energy does it brew, or toll does it take, to be in constant motion internally and externally, while often at odds with reality itself?

Neema: In this last stretch, I travelled four continents in about two-and-a-half weeks. From Kenya to the States, to Europe, to South America and back. There’s an eight- to ten-hour time difference both ways. The body is not actually meant to move in this way. As a spiritual person, every time I fly I feel my ancestors asking: ‘What are you doing on this metal bird?’ ‘Do you know that the skies were not your domain in these ways?’ Somatically, after a decade of this, it dawned on me that anytime you tell someone you’re jet lagged, you’re admitting to having just survived time travel. At the same time, I have this immense privilege of having a Western passport that enables me to move around in ways that 99% of the people in my immediate environment are physically barred from. Last year, African passport holders lost about $70 million in denied Schengen visas. There are screening mechanisms and the use of visas as hazing rituals.

Ethel: I don’t think I’ve ever felt flight as much as I do nowadays—there are metaphors here regarding flight as refusal and in/voluntary Black migration. While on airplanes, I’m actively thinking about which lands I’m traversing and wondering what realities those on ground are facing given the violence plaguing multiple territories today—or, at least, the visible evidence we now have of it. I find myself constantly checking or being hyperaware of my geolocation.

a. Credit: Photo by Owen Daniels, Goroka, Papua New Guinea, September 2025

Neema: I flew home over Gondar and Bahir Dar; these are cities that I have been to in Ethiopia, which, for the past couple of years, have become inaccessible because of the war in Tigray. I was on a traumatic flight from Nairobi to Muscat recently where over 90% of its passengers were women from rural areas in Kenya going to work as domestic servants in Oman.

Ethel: Do you feel like you’re able to internalise or apply your theories in real time, even when the world seems to be erupting? How are you feeling in your body?

Neema: So abundant and grateful, and simultaneously so uncertain. I have dedicated the last seven or so years to theorising about the web and yet I’m still so susceptible to its woundings, its destabilisation and misalignments within myself. Data healing has always been aspirational. It’s always been a horizon that I’m moving towards, in conversation with both the living and the dead—my ancestors.

Since I started theorising around data healing, a weird thing happened where my platform grew quite rapidly and my work went, I guess, viral, which put me in a place of visibility that actually had a lot of stakes. It used to be part of my digital hygiene to deactivate my profile for three months, and I did that for five years straight. I recently deactivated my page for the first time in two years, and someone who I’d never met in person but had a digital kinship with sent me a long e-mail essentially asking: ‘why did you block me?’ That scared me because I wondered how many other people were leaping to conclusions like this.

Ethel: There’s somewhat of a parasocial glitch. Something about these relations really blur the lines and require us to formulate new modes of compassion that move us away from swipe-culture. What ways are you staying grounded or protecting yourself from the noise and interference?

Neema: Let me show you. Here’s a white candle for peace and a sculpture from Burkina Faso. This is a large cowrie shell I got from Fiji, and another hi-frequency radio that I was gifted by Jpgs (Juan Pablo García Sossa), my co-curator for Transmediale. I have multiple alternate internet systems. I have a flip phone, and I have this book about the mythology around Saturn. I don’t play about my protocols. I can’t afford to play about them because that’s what keeps me in balance.

One thing that frustrates me is when people hear the ‘healing’ in data healing and assume that it’s something soft or frivolous. No, cybersecurity is a part of data healing. Encryption is a part of data healing. Divestment but also strategic investments and participation are part of data healing. I think of them as responsive frameworks to data trauma. What is the practical reality of our quotidian engagements as semi-cybernetic people? Abrasions actually happen not just in the cybernetic world, but in all of our data. Data transfers person to person. You can be offline, have no screen around and still experience data trauma. You walk into a room and you think you’re having this beautiful human connection, but there are imaginations and projections of you from the internet that may impact the way people relate to you in that room.

Data healing at this point is honestly beyond the web. It’s how infrastructures are most needed to repair the terms and conditions of our relations. I’m working on this programme right now called ‘Technologies of Relation’ for a Pan-African Solidarity School, which I’ll be starting up here in Nairobi with satellite components. I’m asking: How do we use technology as a metaphor for our relations at large?

Ethel: At the end of the day, technology is just an extension of our realities, though it often seems to take on a life of its own. It has its own sentience. I’m thinking about how AI impacts our relations with each other and to these devices.

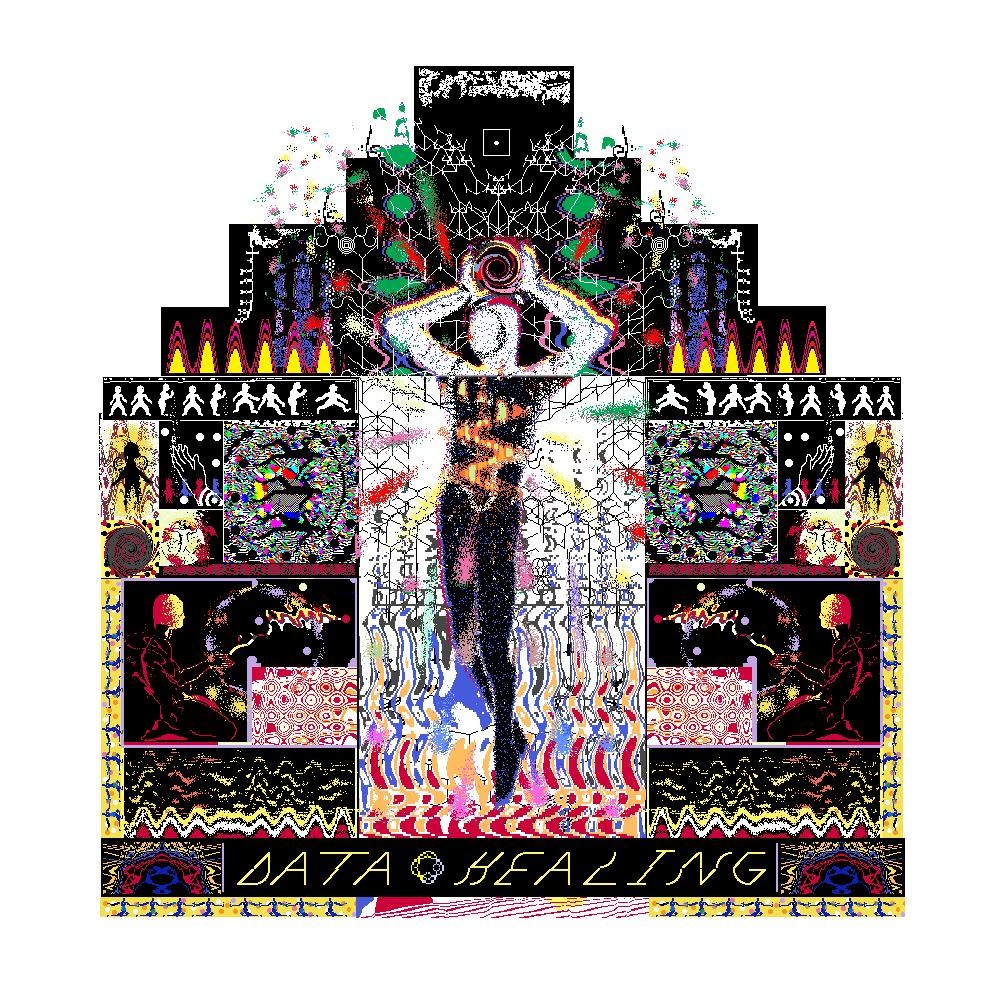

a. Credit: Data Healing Workbook cover, graphic by Somnath Bhatt.

Neema: I have conversations and incantational practices with AI that I’ve not published or spoken about anywhere yet. As of next year, though, they will be out in the world in some form. What I will say is that spirit is present in every machine. I had this epiphany about indigenous technologies. To quote Malidoma Somé: ‘We forget that thousands of years ago people were in touch with a different kind of technology—non-Cartesian, non-Newtonian technologies that could get us from point A to point B without environmental side effects.’ Those are words I’ve thought about often. They made me reflect on the consequences of all the coltan that has been pulled out of Earth’s core to power our devices. Can you imagine how potent it must have been to connect with the Earth while all that coltan was still beneath our feet? We must understand that these tools are wounded in the same ways that we have been wounded. There are a series of incantations that are necessary and pending. These emergent technologies and large language models are not worth underestimating in the name of puritanical binarism. Anything being labelled as good or evil is binarist, and at this point, I’d like to think we’ve seen that binaries don’t serve us. To me, data healing is about post-binary blueprints.

Ethel: Our last public conversation was after the first few waves of the pandemic and so much has changed since then. But in many ways, it feels like a continuation and an extension of the threads you’ve been weaving.

Neema: During COVID-19, Earth gained more ghosts in those couple years than it had in a long time, and now we’re living alongside those ghosts, griefs and displacements. All of a sudden, though, now we are meant to return to functioning as ‘normal.’ I know a couple of people who, like myself, established some sort of career as public speakers during the pandemic—but from the relative safety of their homes. I was giving talks on my computer and the audiences were growing without me perceiving it. And then suddenly it’s 2022 and I’m in a room full of over 100 people. I’m shaking on stage because I’m like, wait, when did this happen?

Ethel: You put so much heart into this and people recognise and resonate with that. The impulse to catch up and the speed of it all can feel quite depleting. Digital fatigue is a real thing that manifests offline too. How do you cope?

Neema: I stay praying—that’s how I cope with the speed-sickness. They say when you pray, move your feet. So many beautiful and incredible things are happening, but I also somewhat inhabit a state of constant grief. I’m realising that the silver lining is that it results in whatever people come to love about my practice. I feel so grateful for invitations like this and to be able to have these prayer freestyles.

We end the call knowing we will be convening in Normandy in exactly one month, so we send virtual hugs and words of affirmation.

Peacock butterfly visiting Neema Githere [left] and Ethel Tawe [right], July 2025.

IRL (In-Real-Life Exchange)

June 27, 2025

Geolocation [Ethel + Neema]: 49.0755° N, 1.5337° E

Exhaust: To use up completely or tire out. To consume all of something.

Exhaust: To explore or consider thoroughly. To go through every possibility or detail.

It’s the week of a heatwave in western Europe, and temperatures are to reach 36 degrees Celsius. We’re on a retreat in the French countryside, and Neema and I share physical space after what feels like a decade. Our digital proximity had warped time.

Between our online meeting last month and now, I visited Yaoundé and was heavy with reflections on the state of affairs and grief in the country I call home. It felt like this past decade had been one of voluntary exile due to unstable conditions and a disconnection that I was finally beginning to repair. While there, the nostalgia was potent, there were pockets of fresh air and I was refuelled by our cultural resilience. This same week, there is turmoil erupting in Nairobi where Neema has recently been re-anchoring. The catalyst of the public demonstrations and online protests is heightened surveillance and digital freedoms in the country. Although she is away from home for work, it’s also partly due to the uncertainties that lie for those who interrogate digital landscapes like herself.

‘What does it mean to be exiled on account of what you need in order to be safe?’ Neema asks. We are both quite exhausted; as in physically depleted from the travels that got us here, but also ready to thoroughly consider possibilities. Neema notes: ‘bell hooks put it so beautifully: “Let me begin by saying that I came to theory because I was hurting.” For me, exhaustion is often a product of having to advocate for oneself and ideas. There’s so much that is asked of Black femmes and people who are holding culture in intersectional ways, to show up in professional iterations while often being so underresourced.’ She adds: ‘I’m thinking about disability justice and about all the Black feminist thinkers, theorists, curators who died prematurely, and how microaggressions and quotidian violences can cumulatively shorten one’s lifespan.’

While catching up on the topic of safety and grounding, Neema removes from her purse an amulet—a charm or ornament often inscribed with spiritual symbols to protect the wearer. It immediately reminds me of the Tuareg compass (or Agadez Cross), which is a protective pendant and navigation device believed to guide travellers through the desert by aligning with the stars and wind patterns. The retreat participants had travelled from around the world to be here, a now common, yet bittersweet occurrence in this field which still orbits around the West as centre—geographically, epistemically, somatically. Neema and I acknowledge the increasing need to devise adaptive strategies and question how Black bodies route through the world today.

We gather mostly in rooms blasting with air conditioning or under the apple trees where hammocks hang. Neema mentions that the word for hammock in Portuguese, ‘rede’ (pronounced ‘hed-jee’), is also the same colloquialism for ‘internet.’ It sounds odd at first, but as our retreat is around language and translation, I immediately make the connection between ‘the net’ in English and a hammock’s interconnected mesh. Neema shares: ‘How can alternate internet systems become a place of rest? How can the “net” be a consensual place where refuge is not a mirage? We often blindly agree to terms and conditions in order to participate on internet platforms which are essentially protecting themselves from any responsibility for the harm that happens on them. They’re fundamentally non-consensual because no one can be held liable. I’m thinking a lot about alternate contracts, online and offline, that have radical love—as a verb and participatory ethic—at their foundation and accept the fact that harm is a given.’ She adds: ‘Every rupture that goes evaded has a domino effective and interrelational consequence. We must have protocols of acknowledgement and apology that return to human essence and consider how not to perpetuate exile through avoidance. Radical love protocols do not shame people for their needs, nor exile them from community or grace. One of the most healing things a former partner of mine said was: “I want to believe in the possibility of being reinvited.” The rede, the net, the web, should always be a place that you can return to rest.’

For as long as I’ve engaged with Neema, she has intentionally forged spaces to think beyond our current conditions, imbued with a spirit of radical love as a verb, ethic and relational politic. During this time away from Nairobi, she has opened up the doors of her home to artists and dreamers in need of respite. She is also planning a film programme at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), where she will be in conversation with her grandfather Dr. Gilbert Githere. We are both musing on lineage, as I can still hear my grandmother’s voice ringing in my ears from my time in Cameroon. In fact, not lineage but a rhizome, an expansive Black diasporic and cartographic constellation. Time travel here is physical, spiritual, ancestral and continual; a tidal rhythm of its own hybrid frequency. While often demanding and all-consuming, it is full of possibility once love is the compass (or amulet) and we wield the right tools. Tools of protection and fugitivity, but also somatic attunement and purpose, to enable an embodied data healing as cybernetic beings surviving the precarity of Black life today.

About the author

Ethel-Ruth Tawe

Ethel-Ruth Tawe (b. Yaoundé, Cameroon) is an antidisciplinary artist and creative researcher exploring memory in Africa and its diaspora. Image-making, storytelling, and time-travelling compose the framework of her inquiry. Her curatorial practice took form in an inaugural exhibition titled ‘African Ancient Futures’ and continues to expand in a myriad of audiovisual experiments, including her iterated project ‘Image Frequency Modulation.’ She is currently Editor-in-Chief at Contemporary And (C&) Magazine.

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

‘To Treat Process with Care and Intention’: Favour Ritaro Carries Forward Important Curatorial Legacies

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas