Macuxi Jaider Esbell: An Indigenous Life Cut Short by Epistemic Extractivism

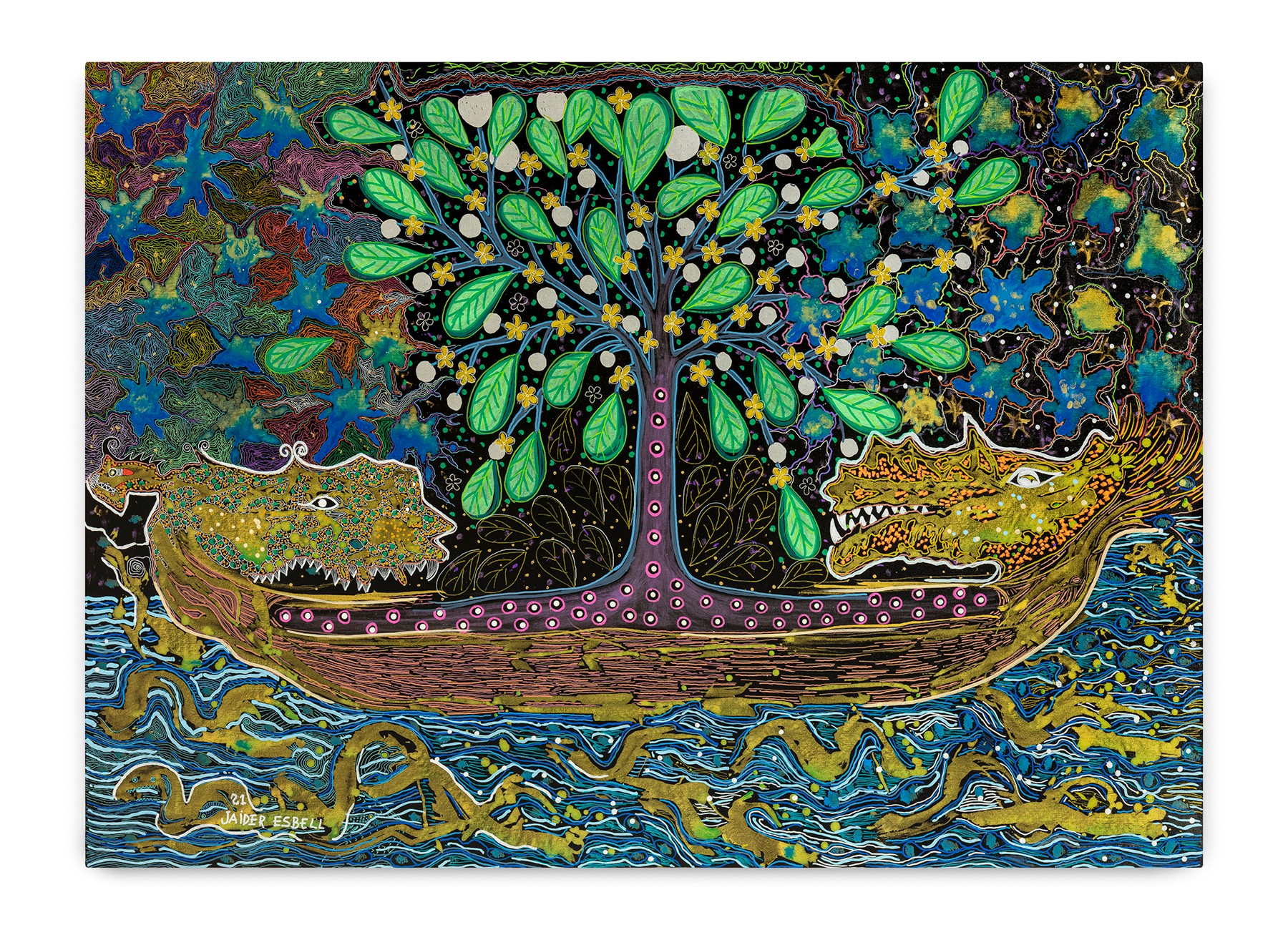

Jaider Esbell, Maikan and Tukui (Foxes and Hummingbirds), 2020. Acrylic and Posca pen on canvas, 100 x 75 cm. Photo: Filipe Berndt / Galeria Millan

05 November 2025

Magazine América Latina Magazine

Words Will Furtado

Translation Zoë Perry

9 min read

The life and work of Jaider Esbell continue to profoundly mark contemporary Brazilian art with his indigenous “artivist” legacy, even after his untimely death. Together with a note from Denilson Baniwa, this text looks back on the artist’s life and questions the price of visibility in a system that continues to consume Indigenous bodies and epistemes.

Macuxi Jaider Esbell passed away voluntarily in 2021 at the age of 41. He was a prominent Brazilian artist, writer, curator, and activist, belonging to the Macuxi people, an Indigenous group from Roraima, in the northern region of the Brazilian Amazon. His work was deeply engaged with themes such as decoloniality, cosmology and indigenous rights, blending cultural heritage with political activism.

Esbell described his practice as “artivism”—a fusion of art and activism aimed at defending Indigenous rights and environmental justice. His multidisciplinary production included painting, writing, performance and curation, often inspired by Macuxi mythology. In his works, he addressed environmental destruction and extractivism, the spiritual and mythological knowledge of the Macuxi and other Indigenous peoples, as well as Indigenous cosmologies as resistance to Western epistemologies. One of his best-known projects is the series A Guerra dos Kanaimés (The War of the Kanaimés), which reinterprets traditional spirits to comment on the contemporary struggles faced by ancestral communities.

Jaider was a fundamental force in the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives on Brazil’s contemporary art circuit. In 2021, he curated the exhibition Moquém_Surárî: Contemporary Indigenous Art, at the Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo (MAM-SP), one of the first major institutional exhibitions in the country with this focus, bringing together 34 artists from diverse backgrounds. That same year, he participated as an artist in the 34th Bienal de São Paulo. He also created and managed the Jaider Esbell Gallery of Contemporary Indigenous Art, in Boa Vista, a space dedicated to promoting indigenous artists from all over Brazil.

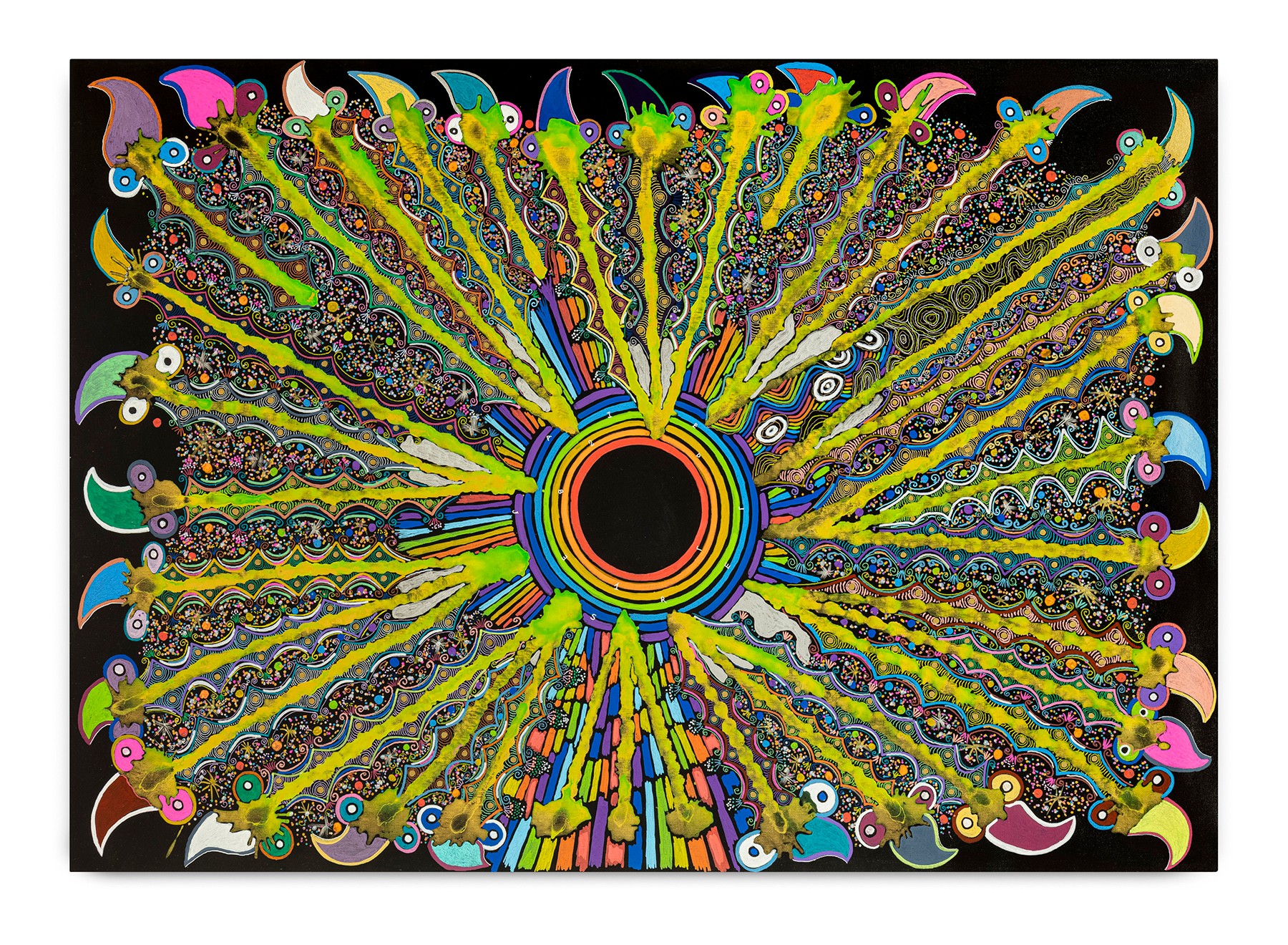

Jaider Esbell, Mereme’ – The Origin of the Rainbow and Its Mysteries, 2021. Acrylic and Posca pen on canvas, 110 x 160 cm. Photo: Filipe Berndt / Galeria Millan

On November 2, 2021, Jaider was found dead in his apartment in São Paulo while participating in the Bienal. His death occurred at a time of great professional recognition and an intense workload. For the 34th Bienal de São Paulo— Faz escuro mas eu canto—Jaider presented, not one, not two, but three works: Guerra dos Kanaimés: a vivid series of paintings depicting ancestral spirits (kanaimés) engaged in contemporary struggles, reflecting the Macuxi resistance for land and culture; Carta ao velho mundo (Letter to the Old World): an intervention in a European art history book, where he superimposed Indigenous graphics and critical commentary, challenging colonial narratives; and Entidades (Entities): a 17-meter inflatable sculpture in the form of serpents, installed at Ibirapuera Park, symbolizing the transformative forces of Macuxi cosmology, in opposition to the statue of the Portuguese invader, Pedro Álvares Cabral.

In March 2021, he held his first solo exhibition in São Paulo, Apresentação: Ruku, at Galeria Millan.

Jaider's workload makes me think of a text published in Hyperallergic, where the American artist Damien Davis questions whether Black visibility is not, in itself, a commodity, due to the way it is valued, as long as it is convenient, and abandoned, if it takes up “too much” space. In relation to Indigenous visibility, this question also fits, and too well. Capitalist epistemic extractivism seems to have no limits, and we only come face to face with its voracity when this same extractivism steals lives from our artistic communities.

Jaider Esbell, The Descent of the Shaman Jenipapo from the Kingdom of Medicines, 2021. Acrylic and Posca pen on canvas, 112 x 160 cm. Photo: Filipe Berndt / Galeria Millan

In the week of his death, his good friend and fellow artist Denilson Baniwa wrote some searing words about the pressures faced in the search for recognition, comparing this journey to a form of captivity, in which Indigenous artists are celebrated and, at the same time, consumed by institutional demands. With Denilson's permission, we publish the full note below:

Hello,

I hope you are strong, even in these difficult times we’re going through.

As you may know, this week we were surprised by the enchantment of Jaider Esbell.

Since he and I met in this world, we have lived and built paths together that were, I think, important for the scene we see today.

He was a friend whom I called “maninho”, an affectionate term for little brother in the region where I’m from. As brothers, we loved each other, we fought, we argued, we played, we traveled together through the heat and cold of the world, we laughed, we cried, we “messed up the bandstand” as they say here, we stopped talking to each other, we started talking to each other again, we worked, we jumped into many rivers and seas, we agreed on many things, we disagreed on many other things, but on one thing we were incorruptible: the desire to build an art, in which Indigenous people could have an active voice and a chance to, who knows, maybe reach the top, a place we’d never been before. Jaider reached that point, and what for white people is considered success (or “the best phase of his career”, as I read in newspaper articles), for the two of us this fake-white-success was becoming a burden day by day. Unfortunately, it was too heavy for him, but it could have been for any of us Indigenous artists. The demand for answers to save art, the pressure not to fail in our journey or with our Indigenous relatives, the uninterrupted hunger of those who see us as a devourable novelty on the market, all of this is considered success. And the height of a career is a wall that surrounds us and takes us away from what is most important: a healthy life.

The moment we felt the hands of the Western world pulling on us, I took a step back to slow down and think about what was happening. First there was social media, which I returned to repeatedly and rebelled against because people called me and sent me messages as a demand that I be online all the time or, worse, be available at all times. So I deleted my number and got a new number just for friends or people I wanted to give my attention to. A few weeks ago, I deleted my social media again, in order to escape the pressures of always being available and being forced to respond to questions like “how to decolonize the world.” Like it was our responsibility: to save the world on our own. Like it wasn’t everyone's responsibility. Oh no! We’re forced to save a world that never wanted us, but when they need us, they turn to us and demand that we be available. It took thirty-two years for the world to pay attention to me. I know that many of the hugs and kisses I receive today are just part of white people's social etiquette. Before that, we only received contempt from this world. But this Indigenous blood that holds grudges and, at the same time, wants to love the world, makes us accept this white label.

I was with Jaider last week. We didn't talk much, because our email and text inboxes were full, our schedules were full. Even though we were together every day for a whole week, from breakfast to bedtime, we spoke very little. And, in the few conversations we did have, we shared the same complaints: a desire to punch the next person who asked us for an online meeting. Jaider was tired. I'm tired. We're tired.

What gets posted on social media doesn’t represent the pain we’re going through on daily basis. Offline, Jaider Esbell wasn’t what was posted. Offline, Denilson Baniwa is far from what you see on Lives. How many Lives have I done, where I forced myself to look well, so I wouldn’t make anyone worry. How many lives have I done literally while sick, with a fever, in pain. But that didn’t get posted. I, and certainly Jaider too, didn’t do this to please white people or become famous. The main reason was to build a path for other Indigenous people, to build possibilities for our own. We were a mirror for those who are Indigenous and still dream of being artists or anything different from the horrific reality that young Indigenous children and youth experience today. We force ourselves to be available to a world that, like Baniwa, I believe is for those yet to be born.

But it’s a heavy burden. Therefore, I ask, with great respect to Jaider and the Indigenous artists past, present, and future, that we ensure that this path we have opened is never blocked, never allowed to become overgrown. May we, you and I, always clear the path and, in the near future, it will be easier to walk along it. Let us cherish the memory of Jaider Esbell. And, above all, let us take care to make our own journey and that of others easier.

Because understanding that, if success and reaching the top—for which we fought so hard—results in tragedy, I feel like I need to think even more about what kind of Indigenous art I should create. And if the reception that the Western art world offered us led one of us to a grave end, I need to think even more about what kind of relationship I want to maintain with that art.

I'm going to slow down even more, to the point that it's a jog and not a triathlon. My work will continue in honor of Jaider Esbell, just as it was in memory of so many other Indigenous relatives before me. If it’s through art that we resist, let it be for art. But for me, it won’t be to satisfy the hunger of any art glutton.

With affection and admiration,

Denilson Baniwa

About the author

Will Furtado

Will Furtado is the Editor-in-Chief of C&AL.

Read more from

Confronting the Absence of Latin America in Conversations on African Diasporic Art

Comigo ninguém pode will be the exhibition that represents Brazil at the Biennale Arte 2026