It’s a complicated relationship

3 Octobre 2016

Magazine C&

6 min de lecture

C& talks to young media artist Isaac Kariuki about the making of zines, the visibility of Black bodies and politics.

C&: What does new technology mean to you in your art practice and also in your private life?

Isaac Kariuki: Technology is something I’m growing more and more reliant and comfortable with in my personal and professional life and I’m still trying to figure out if that is a good or bad thing. I don’t want to be part of the camp that’s pessimistic about technology and the internet’s growing presence in the world. It’s given a lot of people with disabilities, social anxieties and other conditions so much freedom and access that they for example didn’t have six years ago. I was just talking with my friends about how M.I.A.’s album MAYA was released only in 2010 and there were all these themes of state surveillance and paranoia about the internet on the album. This conversation only really took off after Snowden, so basically it’s a complicated relationship.

.

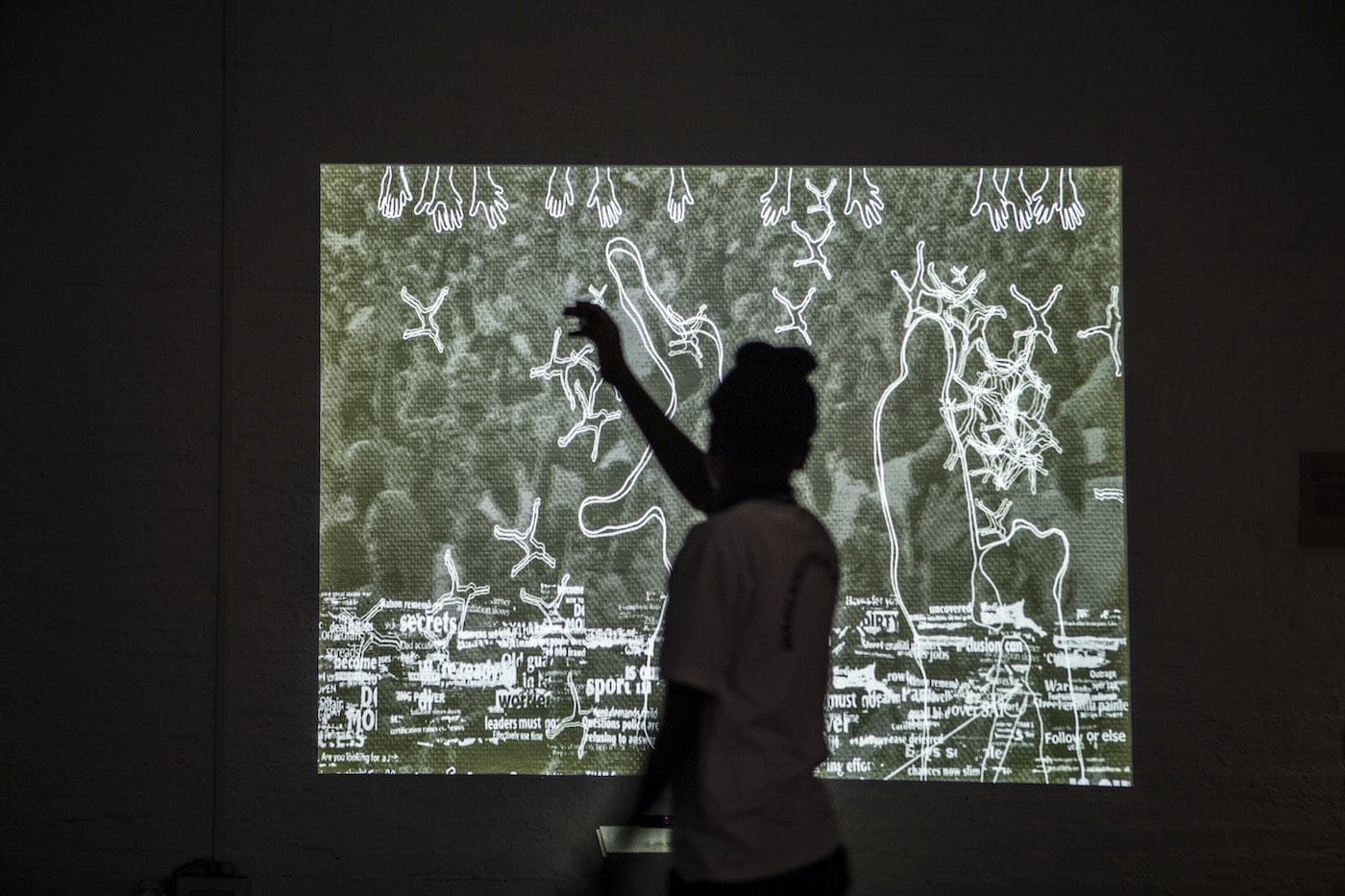

</a> Isaac Kariuki, from the series Weaponise the Internet, OOMK issue 4. Photo. Courtesy of the artist</figure>

.

<b>C&: What kind of stories do you want to tell, convey through your work?</b>

IK: I just tell what I experience and what I know personally, hoping it will resonate with others. My work always comes down to the idea of autonomy. I made a piece for the magazine OOMK called‘Weaponise The Internet’ where I created an imagined Hijabi hacker collective – the idea of people disrupting a structure for their own betterment.

<b>C&: Can you talk aboutthe e-zine Diaspora Drama that you created?</b>

IK: The zine sort of manifested out of my dissatisfaction with the stories young people of color were allowed to share online. I felt like there was a general understanding that we don’t necessarily have quirky and offbeat interests and that really frustrated me because all my friends and the people around me always tell me about something odd they’re researching on or have grown interested in, but they never get a chance to realize this because a lot of places are only interested in rehashed stories of their racial plights and misfortunes. And while this is an obvious thing going on which should have a stage, these are the only stories that do and it becomes very tiring and emotionally draining.

I wanted to create a platform where the less conventional stories get to be told. In the third issue, writer Lilian Min interviewed Annie Wang, the artist who recreated Kim Kardashian’s selfies every day on Instagram. There’s also artists John Yuyi and Tom Galle who created ‘iPhone charger Shoelaces’.

The entire zine has an overarching theme of the internet and technology because young people of color utilize internet culture as a way to form mutual understandings and create a pause from reality that doesn’t demand too much of them.

<b>C&: How do you think can diasporic works and identities be made more visible? And what role do you think social media plays in this?</b>

IK: I don’t think visibility is all that vital or beneficial to us. I’ve been learning this the last few years after some very big moments in the world. I think Black bodies are actually hyper-visible. This was especially obvious during both theGarissa University massacre and the Westgate Mall attack in Kenya where uncensored images of Kenyan bodies were massively circulated in Western news coverage. If that was visibility then it just elevated how desensitized we are to Black people’s suffering.

If we’re talking about visibility in terms of humanity and issues being clearly displayed then I definitely think social media is helping. There’s far less censorship and Africans actually get to say their piece without the surrogacy of a legacy news outlet. Hashtags such as #ThisFlag and #WhatIsARoad are clearly demonstrating this. But this shouldn’t gloss over the countless stories of governments shutting down Twitter and Whatsapp during election seasons and all that. We still have a long way to go but our resourcefulness on the internet always gets us by.

<b>C&: Can you point at other tech/digital artists from the Diaspora and the continent whom you find interesting?</b>

IK: I loveTabita Rezaire,Bogosi Sekhukhuni and pretty much every artist I’ve had in my zine. I believe in everything they do.

.

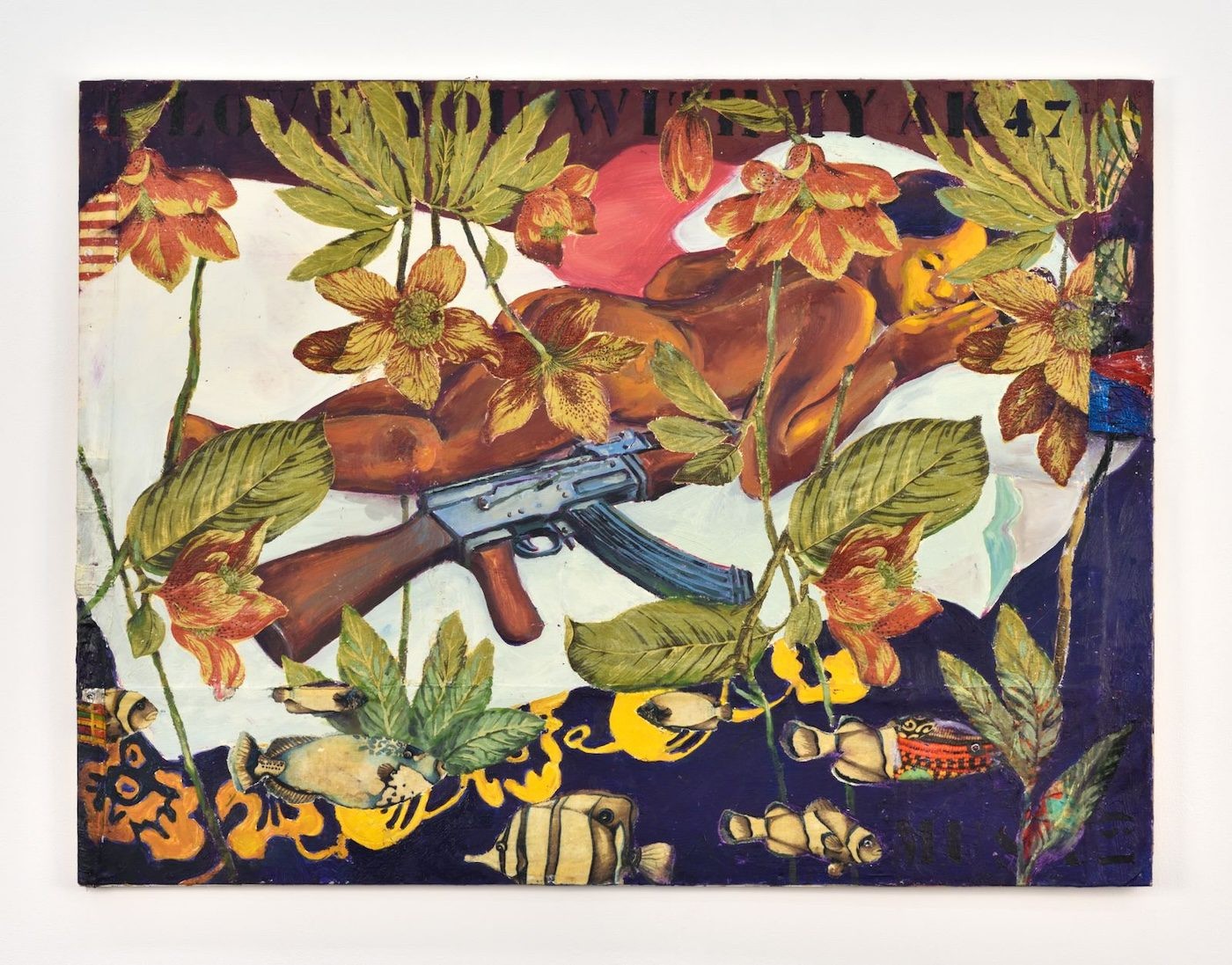

</a> Isaac Kariuki, detail of SIM Card Project, ongoing. Photography and Digital Art. Courtesy of the artist</figure>

.

<b>C&: Tell us a bit about your ongoing series SIM Card Project.</b>

IK: I always wanted to track the cell phone culture in Kenya and the liberation of owning a phone that connects you to all that information. We’ve had a rapid cell phone boom but it’s burdened by the constant fluctuation of the cell phone carriers’ rates and accessibility, which essentially dictates how much you can communicate with people. I tried mimicking the aesthetic idea of Safaricom (Kenya’s largest provider). They always have very glossy, almost uncanny valley promotional images on their SIM cards. So I thought to replicate them by going to a small town in Mombasa named Mtwapa and taking pictures of people around – unsurprisingly there was heavy Safaricom advertising everywhere. I attached those images to SIM card templates, sort of to humanize, humor and lessen the overbearing, almost sinister presence of cell phone providers. I made plastic models of these SIM cards for the Kampala Biennale, which visitors were welcome to take – though they were too courteous to.

<b>C&: What did you explore for your participation at this year’s Kampala Art Biennale?</b>

IK: The theme is mobility, and in an effort not to make a pun out of the SIM Card series, I also brought in an ageing laptop with a webcam where visitors were instructed to replicate the hand gestures that are on the screen. I’ve always been a fan of participatory art and challenging the idea of ‘not touching the art’.

.Isaac Kariuki's website

.

Interview by Aïcha Diallo

de

En Conversation

Fantômes et images en mouvement : le Black Atlas d’Edward George

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

« Considérer le processus avec soin et intentionnalité » : Favour Ritaro perpétue des legs essentiels en matière de commissariat d’exposition

de

Digital art

A(spora) de Jazsalyn : Sur le corridor Gullah Geechee

Sudan Art Archive Aims to Reclaim a Canon from Afar